Nine states still don't report school COVID-19 data

41 states do report school COVID-19 data, but their reporting still leaves much to be desired. Plus: vaccine distribution and hospitalization data.

Welcome back to the COVID-19 Data Dispatch.

It’s a long issue again. Blame the schools, okay? And the vaccines. And the hospitals. There’s just so much to write about right now, but I was as concise as I could be, I promise.

Our main topic this week is my survey of state data reporting on COVID-19 in K-12 schools. I found that nine states are not reporting any data on this topic, while many other states are reporting case counts with limited context. Plus: new sources to watch on vaccine distribution and an analysis of HHS’s hospitalization dataset.

If you were forwarded this newsletter, you can subscribe here:

National numbers

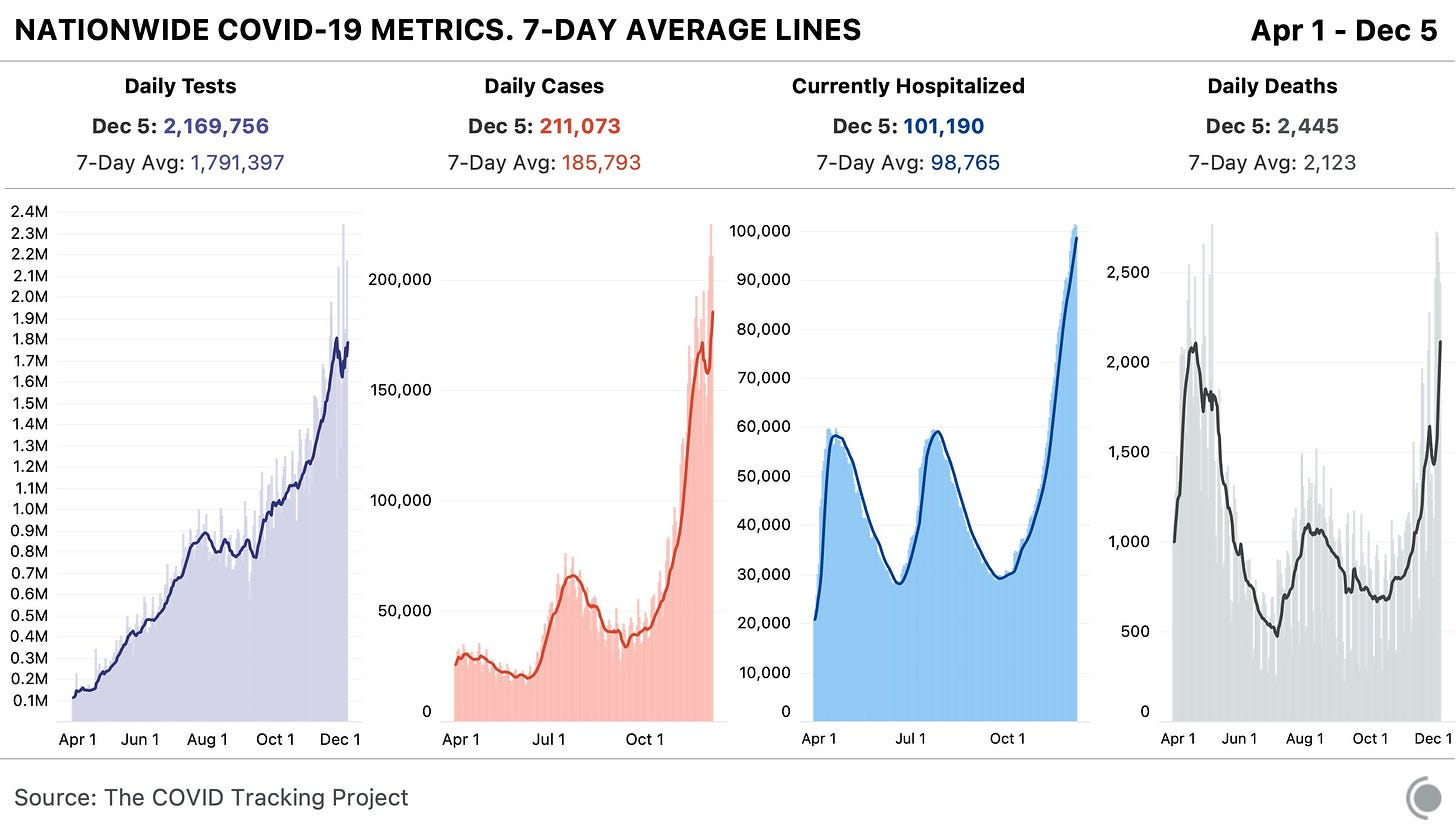

In the past week (November 29 through December 5), the U.S. reported about 1.3 million new cases, according to the COVID Tracking Project. This amounts to:

An average of 186,000 new cases each day (16% increase from the previous week)

297 total new cases for every 100,000 Americans

1 in 252 Americans getting diagnosed with COVID-19 in the past week

9% of the total cases the U.S. reported in the full course of the pandemic

More Americans are getting sick with COVID-19 now than ever before in the pandemic. And this outbreak isn’t isolated. Eleven states broke case records on Thursday, for example, including states in all major regions of the country.

Last week, I warned you about data fluctuations which I expected to see thanks to the Thanksgiving holiday. America first reported fewer cases, deaths, and tests, as public health workers took a day or two off and data pipelines were interrupted. Then, the cases which were not reported over the holiday were added to the count belatedly, culminating in a record of 225,000 new cases on Friday.

If you visit the COVID Tracking Project’s website, you’ll still see a warning notice about these Thanksgiving data disruptions. However, one key number tells us that the pandemic is, in fact, still getting more dire: more patients are getting admitted to the hospital than ever before.

Last week, America saw:

Over 100,000 people now hospitalized with COVID-19 (it’s 101,200 as of yesterday, twice the number of patients at the beginning of November)

15,000 new COVID-19 deaths (5 for every 100,000 people)

To understand the impact of that hospitalization record, read Alexis Madrigal and Rob Meyer in The Atlantic:

Many states have reported that their hospitals are running out of room and restricting which patients can be admitted. In South Dakota, a network of 37 hospitals reported sending more than 150 people home with oxygen tanks to keep beds open for even sicker patients. A hospital in Amarillo, Texas, reported that COVID-19 patients are waiting in the emergency room for beds to become available. Some patients in Laredo, Texas, were sent to hospitals in San Antonio—until that city stopped accepting transfers. Elsewhere in Texas, patients were sent to Oklahoma, but hospitals there have also tightened their admission criteria.

Or, for one doctor’s perspective, read this thread from Dr. Esther Choo:

Deaths are also rising. The deaths of 15,000 Americans were reported last week—the highest number of any week in the pandemic thus far. In fact, COVID-19 was the leading cause of death in America last week, according to the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation.

For past reporting (or to read this issue on Substack), see the archive:

How are states reporting COVID-19 in schools?

Longtime readers might remember that, back in August, I surveyed the available data on how COVID-19 is impacting American schools.

At the time, very few states were reporting school-specific data, even as school systems around the nation began to reopen for in-person instruction. In that early survey, I highlighted only Iowa as a state including district-level test positivity data on its COVID-19 dashboard. This dearth of data disappointed, but did not surprise me. There was no federal mandate for states, counties, or school districts to report such data, nor did the federal government compile such information.

There is still no federal mandate for school COVID-19 data, despite pleas from politicians and educators alike. So, as school systems across the country close out their fall semesters amidst a growing outbreak and prepare for the spring, I decided to revisit my survey. I sought out to find how many schools are reporting on COVID-19 cases in their K-12 schools, which metrics they are reporting, and how often. To get started with this search, I used the COVID Monitor, a volunteer effort run by Rebekah Jones which is compiling K-12 case counts from government sources and news reports.

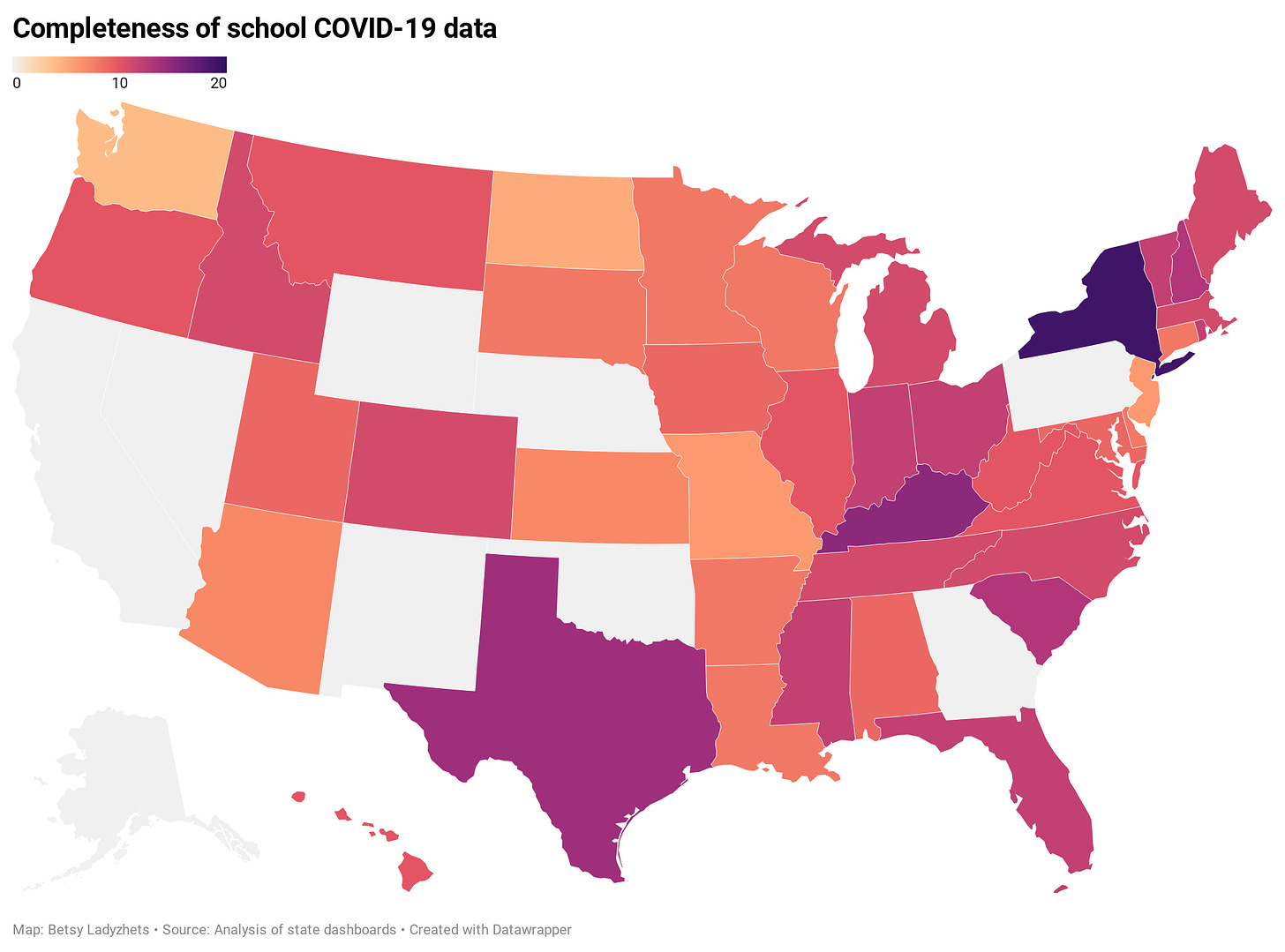

Overall, many more states are providing school data now than in August. But the data are spotty and inconsistent; most states simply report case counts, making it difficult to contextualize school infections. (For more on why demoninators are important in analyzing school data, see my October 4 issue.)

You can see the full results of my survey in this spreadsheet. But here are a few key findings:

In total, 35 states report case counts in all public K-12 schools. 6 states report in an incomplete form, either not including all schools or not including specific case counts.

9 states do not report school COVID-19 data at all. These states are: Alaska, California, Georgia, Nebraska, Nevada, New Mexico, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, and Wyoming.

Most states update their school data either weekly or biweekly. Only 7 states update daily.

Most states do not report counts of deaths and hospitalizations which are connected to school COVID-19 outbreaks. Only 5 states report deaths (Colorado, Kansas, North Carolina, Kentucky, and Virginia), and only 1 state reports hospitalizations (Kansas).

Only 3 states report in-person enrollment numbers: New York, Massachusetts, and Texas.

New York is the only state to report counts of COVID-19 tests conducted for K-12 students and staff.

And here are a couple of example states I’d like to highlight:

New York has the most complete school data by far, scoring 19 out of a possible 21 points on my index. Not only does the state report enrollment and total tests administered to students and staff, New York’s COVID-19 Report Card dashboard includes the test type (usually PCR) and lab each school is using. Test turnaround times are also reported for some schools. This dashboard should be a model for other states.

Indiana has a dashboard that I like because it is easy to find and navigate. You don’t have to search through PDFs or go to a separate dashboard—simply click on the “Schools” tab at the top of the state’s main COVID-19 data page, and you will see cumulative case counts and a distribution map. Clicking an individual school on the map will cause the dashboard to automatically filter. Indiana also reports race and ethnicity breakdowns for school cases, which I haven’t seen from any other state.

Texas provides detailed spreadsheets with case counts and on-campus enrollments for over 10,000 individual schools. The state reports new cases (in the past week), total cases, and the source of school-related infections (on campus, off campus, and unknown). The infection source data suggests that Texas is prioritizing schools in its contact tracing efforts.

Minnesota is one state which provides incomplete data. The state reports a list of school buildings which have seen 5 or more COVID-19 cases in students or staff during the past 28 days. Specific case counts are not provided, nor are specific dates on when these cases occurred. If I were a Minnesota parent at one of these listed schools, I’m not sure what I’d be able to do with this information beyond demand that my child stay home.

As cases surge across the country, more children become infected, and school opening once again becomes a heated debate from New York City to North Dakota, it is vital that we know how much COVID-19 is actually spreading through classrooms. How can we decide if school opening is a risk to students, teachers, and staff if we don’t know how many students, teachers, and staff have actually gotten sick?

Moreover, how can we understand the severity of this threat without enrollment or testing numbers? Reporting that a single school has seen three cases is like reporting that a single town has seen three cases; the number is worth very little if it cannot be compared to a broader population.

Volunteer sources such as the COVID Monitor and Emily Oster’s COVID-19 School Response Dashboard are able to compile some information, but such work cannot compare to the systemic data collection efforts that national and state governments may undertake. If you live in one of those nine states that doesn’t report any school COVID-19 data, I suggest you get on the phone to your governor and ask why.

Also, speaking of New York City, here’s an update to the 3% threshold I reported on last week:

This newsletter is a labor of love for me each week. If you appreciate the news and resources, I’d appreciate a tip:

Vaccine news: data and concerns on early distribution

Everyone in the science communication world is talking about COVID-19 vaccines right now. I’ve attended three vaccine webinars in the past week alone.

We’re all gearing up for next Thursday, when the FDA’s Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee will meet to discuss Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) for Pfizer and BioNTech’s vaccine. If the vaccine is authorized for distribution, doses will go out to every state within days. Meanwhile, Moderna’s vaccine continues to demonstrate promising results. Moderna has also applied for EUA; FDA’s committee will meet to discuss this candidate on December 17.

Here are a few major data sources and issues that I’ll be watching as these vaccine candidates progress:

The CDC has recommended that the first available vaccine doses go to healthcare workers and residents of long-term care facilities (nursing homes, assisted living facilities, etc.) The agency did not specify how state and local governments should prioritize among these groups.

How many people are actually in those high-priority groups in each state? To answer that question, see the Vaccine Allocation Planner for COVID-19, a new data tool from the Surgo Foundation, Ariadne Labs, and other collaborators. For each state, the tool uses population estimates from the Census, the CDC, and other sources to show how many healthcare workers, first responders, teachers, people with severe health conditions, and other high-risk individuals will need to be vaccinated. The tool is automatically set to calculate each state’s available doses as a population-adjusted share of 10 million, but users can adjust it to see how different scenarios may play out.

How many vaccine doses are actually going to each state? To answer this question, see the new COVID-19 Vaccine Allocation Dashboard from Benjy Renton. Renton is compiling information from local news sources on dose distributions from Pfizer and Moderna’s early shipments. Remember that both of these vaccines require two doses per person. In Texas, for example, the first Pfizer shipment of 224,250 doses will allow about 11 in every 1,000 Texas to get vaccinated.

How will vaccination be tracked? The CDC has promised to set up a national dashboard similar to its flu registry, but until then, we must rely once again on state data. This CDC list of state immunization registries should be a useful starting point for any local reporters hoping to get a jump start on vaccine data. You’d better believe that I will be spending a lot of time with these registries in future issues.

The Kaiser Family Foundation is setting up a new dashboard to track public opinion on COVID-19 vaccines. This initiative, called the COVID Vaccine Monitor, will compile the results of regular focus groups and surveys on whether Americans plan to get vaccinated and why. The dashboard is not live yet, but you can learn more about it and hear past KFF findings in the foundation’s December 3 briefing. One notable statistic: 67% of Black adults are “not too confident” or “not at all confident” that vaccines will be distributed fairly, as of a KFF poll conducted in August-September.

For vaccine coverage outside the U.S., see this map of procurement data from the Launch & Scale Speedometer. This research group from the Duke Global Health Innovation Center has compiled the total vaccine doses purchased by over 30 nations. The dashboard also estimates the share of each nation’s population it could be able to cover with advanced vaccine purchases. Canada is highest on the scale at 601%; the nation’s extra doses will likely be donated to other countries.

STAT’s Helen Branswell has written a comprehensive feature on the vaccine-related challenges that lie ahead. Some of the big challenges: coordinating a speedy early rollout, overcoming vaccine distrust, distributing vaccine doses equitably, protecting vulnerable populations (such as pregnant women and children) on whom vaccine candidates have not yet been tested, and continuing to study additional vaccines once the first candidates to win EUA are rolled out.

What questions do you have around COVID-19 vaccines?

It’s time for our next brief reader survey, and this time, I want to hear your vaccine concerns. As this continues to be a major coverage topic for me, I’d like to be sure I’m prioritizing the needs of my readers in choosing specific vaccine-related issues and data sources to investigate.

This is a one-question survey. A few reader respones (from those who indicate they’re comfortable with it) will be shared next week.

HHS’s hospitalization data are good, actually

In July, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) took over collecting and reporting data on how COVID-19 is impacting America’s hospital systems. This takeover from the CDC—which had reported hospitalization data since the start of the pandemic—sparked a great deal of political and public health concern. Some healthcare experts worried that a technology switch would put undue burden on already-tired hospital workers, while others worried that the White House may influence the HHS’s data.

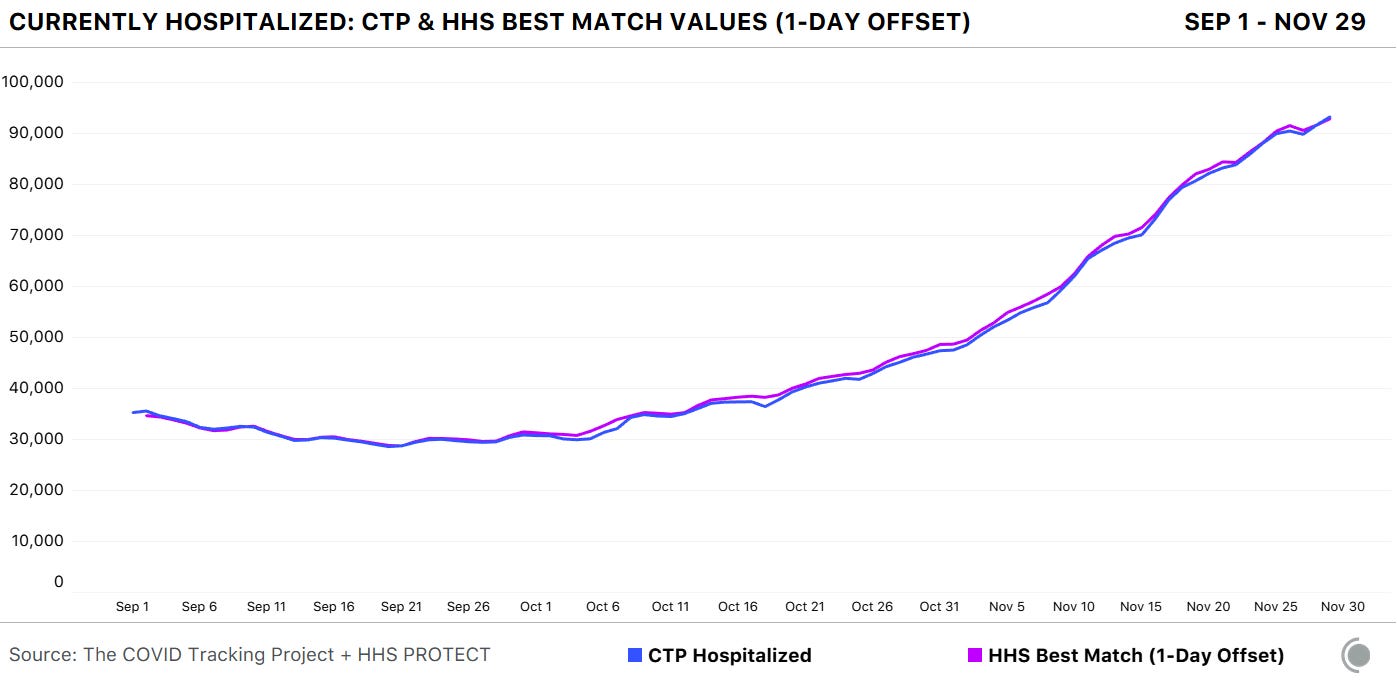

Since that data responsibility switch, I’ve spent a lot of time with that HHS dataset. In August, I wrote a blog post for the COVID Tracking Project which compared HHS’s counts of hospitalized COVID-19 patients to the Project’s counts (compiled from states). At the time, my co-author Rebecca Glassman and I observed discrepancies between the datasets, which we attributed in part to differences in definitions and reporting pipelines. For example: some states only report those hospital patients whose cases of COVID-19 have been confirmed with PCR tests, while HHS reports all patients (including those with confirmed and suspected cases).

I’ve covered the HHS hospitalization dataset several times in this newsletter since, including its investigation by journalists at ProPublica and Science Magazine and its expansion to include new metrics. The dataset has gone from a basic report of hospital capacity in every state to a comprehensive picture of how the pandemic is hitting hospitals. It includes breakdowns of patients with confirmed and suspected cases of COVID-19, patients in the intensive care unit (ICU), and patients who are adults and children. As of November, it also includes newly admitted patients and staffing shortages. At the same time, HHS officials have worked to resolve technical issues and get more hospitals reporting accurately in the system.

A new analysis, published this past Friday by the COVID Tracking Project, highlights how reliable the HHS dataset has become. The analysis compares HHS’s counts of hospitalized COVID-19 patients to the Project’s counts, compiled from states. Unlike the analysis I worked on in August, however, this recent work benefits from HHS’s expanded metrics and more thorough documentation from both the federal agency and states. If a state reports only confirmed cases, for example, this number can now be compared directly to the corresponding count of confirmed cases from the HHS.

Here’s how the two datasets line up, as of November 29:

Since November 8, in fact, the two datasets are within two percent of each other when adjusting for definitional differences.

The blog post also discusses how patient counts match in specific states. In 41 of 52 jurisdictions (including the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico), the two datasets are in close alignment. And even in the states where hospitalization numbers match less precisely, the two datasets generally follow the same trends. In other words: there may be differences in how the HHS and individual states are collecting and reporting their numbers, but both datasets tell the same story about how COVID-19 is impacting American hospitals.

I recommend giving the full blog post a read, if you’d like all the nerdy details. Alexis Madrigal also wrote a great summary thread on Twitter:

This new COVID Tracking project analysis comes several days after an investigation in Science Magazine called the HHS dataset into question. The investigation is based on a CDC comparison of these same two datasets which doesn’t account for the reporting differences I’ve discussed.

Charles Piller, the author of this story, raises important questions about HHS’s transparency and the burden that its system places on hospitals. It’s true that the implementation of HHS’s new data reporting system was rolled out quickly, faced technical challenges, and caused a great deal of confusion for national reporters and local hospital administrators alike. The HHS dataset deserves the careful scrutiny it has received.

But now that this careful scrutiny has been conducted—and the two datasets appear to tell the same story—I personally feel comfortable about using the HHS dataset in my reporting. In fact, I produced a Stacker story based on these data just last week: States with the highest COVID-19 hospitalization rates.

Featured sources

These sources, along with all others featured in previous weeks, are included in the COVID-19 Data Dispatch resource list. Please note that I took state school data sources out of this document because my COVID-19 state school data survey provides a more comprehensive view of these data.

Allocating Regeneron’s treatment: On November 21, Regeneron’s monoclonal antibody treatment received Emergency Use Authorization from the FDA. A new dataset from the HHS shows how this drug is being allocated to states and territories. For more information on the dataset, see HHS’s November 23 press release.

COVID-19 relief tracker: The Project on Government Oversight (POGO) has a new tracker which shows where COVID-19 relief funds from the federal government have been spent. The dashboard visualizes data from USAspending.gov, and is searchable by state, county, and ZIP code.

Census COVID-19 Demographic and Economic Resources: My coworker Diana Shishkina recently alerted me to a Census page which compiles and visualizes a great deal of data on how COVID-19 has impacted Americans. It includes data from weekly small business surveys, the Household Pulse Survey, and a wealth of other information.

COVID source callout

Look, I like Wyoming’s COVID-19 dashboard. I like that it’s not actually one dashboard, but five dashboards—one for cases, one for deaths, one for tests, one for hospitals, one for county-level data—each of which has its own update schedule. I like that I need to hover over bars and download crosstabs in order to obtain precise figures. I like that sometimes the percentages add up to 100% and sometimes they don’t.

I find it charming to need five or six tabs open every time I check the state. It’s a nice challenge. Those states that include all their data on one page, they make things too easy!

More recommended reading

Stacker Science & Health coverage

News from the COVID Tracking Project

As North Dakota’s Deaths Metrics Diverge, We’re Switching to a Less Backlogged Measure of Fatalities

Hospitalizations Break 100,000, Holiday Data Stalls Out: This Week in COVID-19 Data, Dec 3

Bonus

The Pandemic Heroes Who Gave us the Gift of Time and Gift of Information (Insight by Zeynep Tufekci)

Wrong Masks and ‘Missing’ Ventilators: NYC’s Billion-Dollar COVID Gear Bungle (The City NY)

The words that actually persuade people on the pandemic (Axios)

2 Mass. Prisoners Hospitalized With COVID-19 Die A Day After Being Granted Medical Parole (WBUR)

Borscht

The people have spoken, and so I am sharing the Ladyzhets family borscht recipe here even though it has nothing to do with COVID-19 data. Please send pics if you try it.

That’s all for today! I’ll be back next week with more data news.

If you’d like to share this newsletter further, you can do so here: