Hospital capacity dataset gets a makeover

The Department of Health & Human Services (HHS) has taken over from the CDC in collecting and disseminating data about the burden COVID-19 is placing on U.S. hospitals.

Welcome to the first issue of the COVID-19 Data Dispatch! Thanks for being here, I’m excited to be yelling about data issues with all of you.

This first issue will focus on hospital utilization; I’ll explain the recent switch from a CDC-run dataset to an HHS-run dataset from the perspective of a journalist attempting to report stories based on these data. Then, I’ll recommend a couple of other stories on COVID-19 data and datasets for you to explore.

This is a brand-new newsletter, so I would appreciate anything you can do to help get the word out. If you were forwarded this email, you can subscribe here:

A federal hospital capacity dataset is now available on the HHS Protect portal—but can we use it?

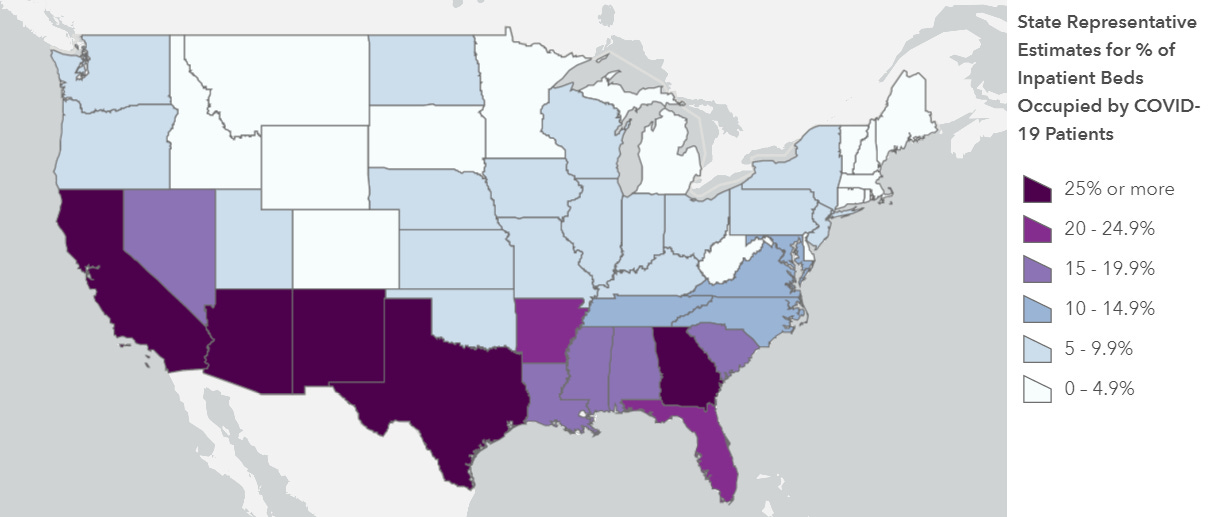

Screenshot retrieved from the HHS Protect Public Data Hub on July 26, 2020

On July 14, the White House announced that hospitals across America would no longer report their COVID-19 patient numbers and supply needs to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Instead, they would report numbers through a data portal set up in April by the Department of Health & Human Services (HHS). A July 10 guidance issued by HHS requests that hospitals send reports on how many overall patients they have, how many COVID-19 patients they have, the status of those patients, and their needs for crucial supplies such as PPE and remdesivir.

In some ways, this switch actually makes sense: HHS’ data portal, built by a contractor called TeleTracking, is designed specifically to support more efficient data collection during COVID-19. HHS was already collecting hospitalization data second-hand through state reports, some hospital-to-HHS reports, and the CDC’s old system, called the National Healthcare Safety Network; the new system is more streamlined at the federal level. HHS is also the primary federal entity collecting data on COVID-19 lab test results, through reports that go directly from laboratories to HHS (often bypassing local and state public health departments).

Simplifying data collection to one office—just HHS, rather than HHS and CDC—should theoretically make it easier for hospitals to report their needs and receive aid from the federal government quickly. But switching systems during the middle of a pandemic is dangerous. Switching systems during a COVID-19 surge in the Sun Belt when hospitals are being pushed to their full capacity is especially dangerous. Hospital databases, once set up to report to the CDC, must be reconfigured—or worse, exhausted healthcare workers must manually enter their numbers into the new system.

STAT News’ Nicholas Florko and Eric Boodman explore this issue in more detail, but here is one quote from John Auerbach, president and CEO of Trust for America’s Health, which summarizes the problem:

Hospitals are incredibly varied across the country in terms of their capacity to report data in a timely and accurate way. If you’re going to say every hospital, regardless of its size, its resources, its capacity, has to learn a new system quickly, it’s problematic.

It is inevitable that, for the first few weeks of this new system, any hospital capacity data reported by HHS will be rife with errors. And yet, public health leaders, researchers, and people simply living in Texas and Florida need to know how their hospitals are doing right now, so HHS has published the results of their new reporting system only a week after the ownership shift. The new website HHS built to publish these data, called the HHS Protect Public Data Hub, went live this past Monday, July 20. (Veteran users noted that this page copied the homework of the dataset’s former home on the CDC website—same color scheme and everything.)

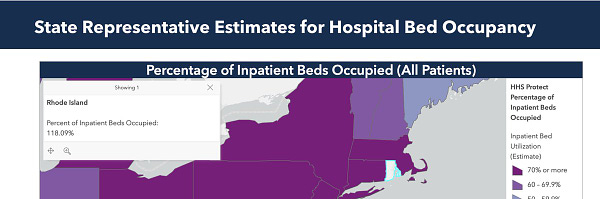

As I send this newsletter, the HHS Protect dataset was most recently updated on Thursday, July 23 with data as of the previous day. Experts looking at these data, including my fellow volunteers at the COVID Tracking Project, quickly noticed that something seemed off:

You read that right: according to HHS Protect, 118% of Rhode Island’s hospital beds are currently occupied. As are 123% of its intensive care beds. And that’s just an extreme example; when one compares the hospital capacity estimates in this HHS update to the most recent estimates from the CDC’s system (dated July 14), only 6 states do not show changes of at least 20%. New Mexico, for example, has supposedly seen its number of COVID-19 patients skyrocket 265% in eight days’ time.

Yes, the HHS system is collecting figures from about 1,500 more hospitals than the CDC system did. And yes, 21 states are currently listed as having “uncontrolled spread” by public health research group COVID Exit Strategy. But hospitalization figures typically rise slowly, with a slight delay from cases; for journalists like myself who have been looking at this data point for months, the jump reported by HHS is simply not reasonable.

It’s good news for journalists and public health leaders that hospital capacity data is once again publicly available from a standardized, federal source. But I have a lot of questions for HHS. What is the agency doing to support already-taxed hospitals that do not have the staff or resources to transfer their database systems? When hospitals inevitably submit their data with errors, what protocols are in place to catch these issues and ensure all data going out to the public portal is accurate? How will the new system support state public health departments, such as Missouri and South Carolina, that previously relied on the CDC for their hospitalization figures? Will HHS make other datasets available on the HHS Protect portal (such as lab data), and if so, when?

A fellow volunteer from the COVID Tracking Project and I are drafting a strongly worded email to HHS’s press team including these questions and many more; I hope to have some answers for you by next week. In the meantime, you can read Stacker’s story on hospital capacity by state, which does not cite the new HHS figures. Don’t ask me how many times I had to update the story’s methodology.

Public health experts call for COVID-19 data standardization

The U.S. urgently needs better standards for COVID-19 data at national, state, and local levels, argues Resolve to Save Lives, a nongovernmental initiative run by the global health organization Vital Strategies. Resolve is led by President and CEO Dr. Tom Frieden, a former Director of the CDC; he worked with other public health experts on a report which reviewed the availability of COVID-19 data in the U.S.

According to Resolve’s report, only 40% of “essential data points” for monitoring COVID-19 are publicly made available by federal and state sources. These data points include new confirmed and probable cases, the share of new cases linked to another new case (through known outbreak sites and contact tracing), and hospitalization per capita rates. Moreover, state dashboards are so disparate in their information presented and functionality that it is incredibly difficult to compare key metrics and get a full picture of the national outbreak.

As a volunteer who works on data quality for the COVID Tracking Project, I am intimately familiar with this problem, but Dr. Frieden describes it better than I do:

The lack of common standards, definitions, and accountability reflects the absence of national strategy, plan, leadership, communication, or organization and results in a cacophony of confusing data. By tracking essential metrics publicly in all states, we can build the transparency and accountability essential to make progress.

Check out Resolve’s report on essential indicator availability by state to see where your state stands, and then, in a free moment between calling your government representatives, call your public health department and insist that they do better.

Which COVID numbers you should pay attention to, actually

My last big story for this week is to heavily recommend this ProPublica feature by Caroline Chen and Ash Ngu on how to navigate COVID-19 data. Chen is a veteran health journalist who has been reporting on COVID-19 since January (and who reported on previous disease outbreaks before that). Her story explains how to understand test positivity rates, data lags, and the inherent uncertainty that comes with any attempt to quantify this pandemic.

You should really read the full story, but I’ll summarize the main points for you here in case you’re just going to bookmark it for later:

Test positivity rates indicate the share of COVID-19 tests in a region which are coming back positive. If the rate is high (above 10%), this may mean only sick people have access to tests, and testing is not occurring widely enough to fully capture the scale of an outbreak. If the rate is low (below 5%), this may mean anyone who wants a test can get one, and epidemiologists will be able to quickly identify and trace new outbreaks.

Daily case counts often are not a good indicator of how a region’s outbreak is progressing, because counts of new cases may be undercounted on weekends or during testing delays. For a more accurate picture, look at the seven-day rolling average—a figure that averages a particular day’s number of new cases with the numbers of the six previous days. Also, rises in deaths tend to lag rises in cases by several weeks, reflecting the progression of the disease in COVID-19 patients.

It is difficult to state definitively whether a certain event—such as a restaurant opening or a protest—impacted COVID-19 spread in an area. No one event occurs in a vacuum, and any resulting data around that event were likely impacted by testing lags, testing availability, and other factors.

Don’t just look at one statistic; look at the whole picture. Ask whether case counts are rising in your area, yes, but also ask: are enough people getting tested? Are the hospitals filling up? How does your state or county compare to others nearby?

Find and follow sources you trust to help you interpret data as they are released. A good source will advise you in the areas where they have expertise and let you know when a question is out of their wheelhouse.

Featured data sources

The COVID Racial Data Tracker, by the COVID Tracking Project: COVID-19 is killing Black Americans at 2.5 times the rate of white Americans. The COVID Racial Data Tracker (or CRDT) keeps tabs on this disparity and others by collecting case and death counts, broken down by race and ethnicity, from state COVID dashboards. Our dataset is updated twice a week. And I say “our” because I work on this dataset; I’m happy to answer questions about it (betsyladyzhets@gmail.com).

Excess deaths associated with COVID-19 (U.S.): One dataset which the CDC hasn’t stopped publishing is a tally of the death toll in the U.S., including deaths which may be directly or indirectly related to the pandemic but have not been reported due to insufficient testing. The dataset is updated weekly, and you can see figures broken down by state and different demographic factors.

Excess deaths associated with COVID-19 (international): The Economist compiles a similar dataset to the CDC, tracking excess deaths in countries and cities around the world. You can read about and see visualizations based on these data here.

COVID source callout

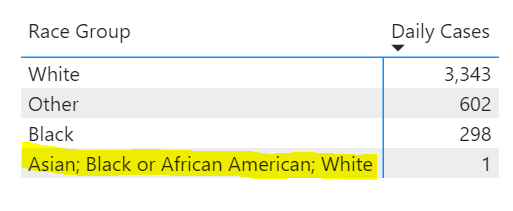

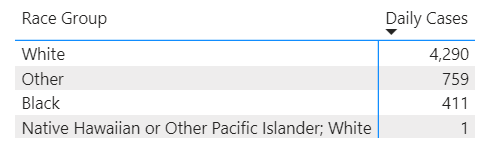

I have issues with West Virginia’s race data.

First, West Virginia insists on reporting COVID-19 cases assigned to racial categories which do not exist. Two weeks ago, this was a category labeled, “Asian; Black or African American; White.” Last week, this was a category labeled, “Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander; White.” The categories are particularly curious because WV usually only reports their cases according to three race categories: White, Black, and Other.

(These extra categories have since disappeared from WV’s COVID Dashboard.)

Relatedly, WV’s race data for cases is listed in a rather unintuitive location on the state’s dashboard: on a page labeled “County Summary.” If you did not look closely, you would think they weren’t reporting demographic data at all.

And finally: WV used to report demographic information for deaths due to COVID-19 which occurred in the state. This information has not been reported since May 20. Sure, WV’s outbreak has been relatively small (with a total of 5,887 cases and 103 deaths as of July 26), but this is no excuse for failing to report the impacts of this outbreak on marginalized communities. According to CRDT figures, Black West Virginians make up 4% of the state’s population, but comprise 8% of its COVID-19 cases. To present a complete picture, the state should report death counts as well as the impacts of COVID-19 on other racial groups.

More recommended reading

My recent Stacker bylines

News from the COVID Tracking Project

Erratic Hospital Numbers, Deaths Still Rising: This Week in COVID-19 Data, July 23

Florida’s COVID-19 Data: What We Know, What’s Wrong, and What’s Missing

Bonus

To Navigate Risk In a Pandemic, You Need a Color-Coded Chart (WIRED)

Race and America: why data matters (Financial Times)*

*paywalled; I can send a PDF to anyone interestedThe explosion of new coronavirus tests that could help to end the pandemic (Nature)

That’s all for today—thanks for reading!

If you’d like to share this baby newsletter further, you can do so here:

And if you have any feedback for me, you can send me an email (betsyladyzhets@gmail.com) or comment on the post directly: