Who gets vaccinated first?

1 in every 82 Americans has been diagnosed with COVID-19 since the beginning of November. Vaccines are coming, but there are many potential pitfalls before they reach your community.

Welcome back to the COVID-19 Data Dispatch—where, vaccine distributors, we are watching you.

This week’s issue is all about vaccines. I explain who should get inoculated first, and how we can hold our public health authorities accountable in the process. I also explain the complexities in AstraZeneca and the University of Oxford’s early results. Plus, why you should be wary of data patterns this Thanksgiving weekend, the discrepancy complicating NYC’s school closure, and an argument for better contact tracing numbers.

If you were forwarded this newsletter, you can subscribe here:

Warning about today’s newsletter: she’s long! You might find that it is “cut for length” in your inbox. If you want to open this in a new tab and get back to it later, you can find it on my Substack archive site here:

National numbers

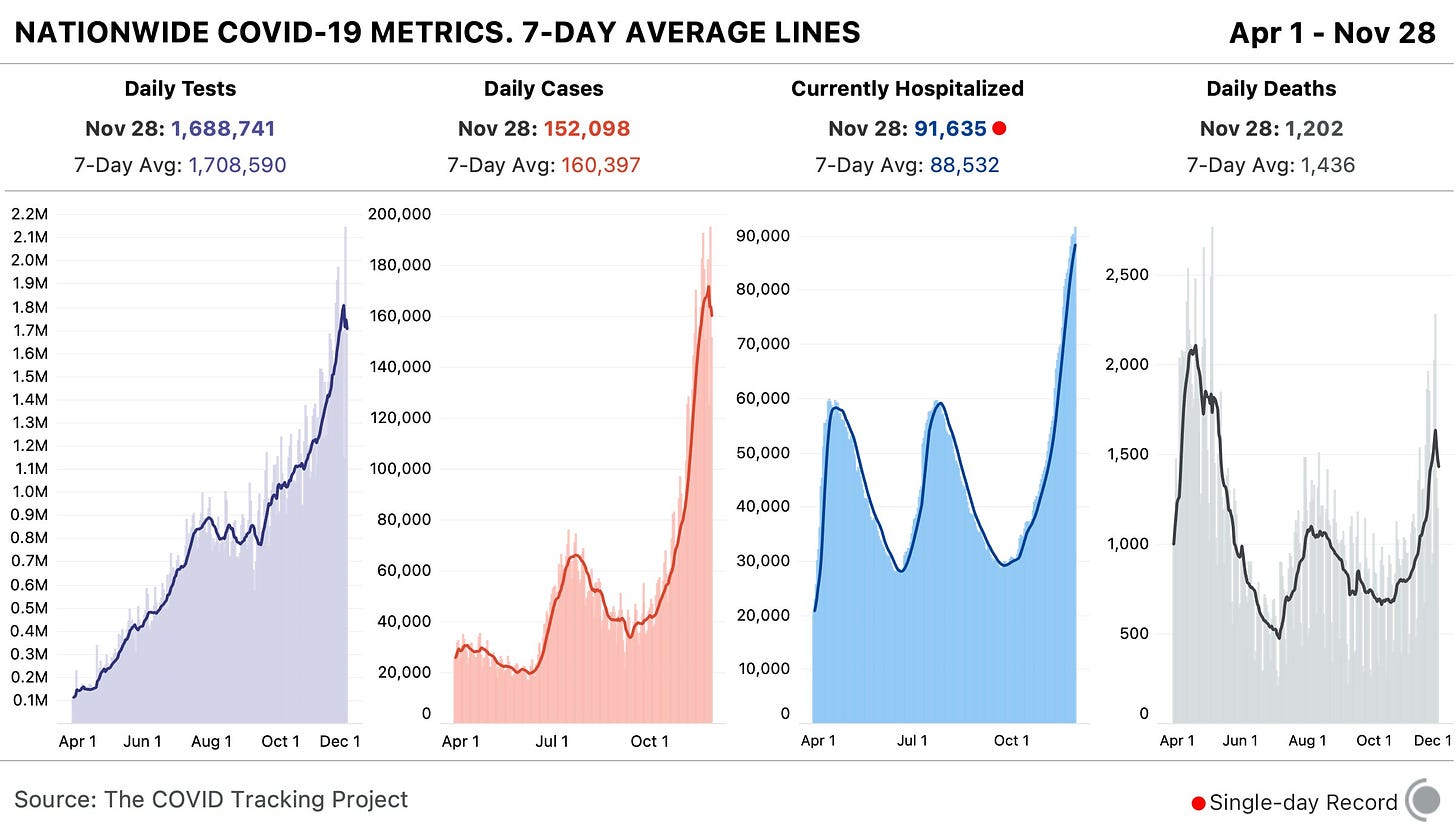

In the past week (November 22 through 28), the U.S. reported about 1.1 million new cases, according to the COVID Tracking Project. This amounts to:

An average of 160,000 new cases each day (4% decrease from the previous week)

343 total new cases for every 100,000 Americans

1 in 292 Americans getting diagnosed with COVID-19 in the past week

9% of the total cases the U.S. reported in the full course of the pandemic

1 in every 82 Americans has been diagnosed with COVID-19 since the beginning of November. Sit with that number for a minute. Picture 82 people. Imagine one of them getting sick, going to the hospital, having debilitating symptoms for months afterward. That is the weight of this pandemic on America right now.

The COVID Exit Strategy tracker now categorizes the virus spread in every state except for Maine, Vermont, and Hawaii as “uncontrolled,” and even those three states are “trending poorly.” I know we just finished an exhaustive public health news cycle about Thanksgiving travel, but… I would recommend that you start making your Christmas plans now.

America also saw:

10,000 new COVID-19 deaths last week (3.1 per 100,000 people)

91,600 people currently hospitalized with the disease, as of yesterday (93% increase from the start of November)

This week, though, I need to caveat the data pretty heavily. The public health officials who collect and report COVID-19 numbers celebrate holidays just like the rest of us; but when dashboards go dark for a day or two, those data gaps can lead to some weird trends.

Here’s how COVID Tracking Project lead Erin Kissane explains it, in a recent Project blog post:

First, by Thanksgiving Day and perhaps as early as Wednesday, all three metrics [tests, cases, and deaths] will flatten out or drop, probably for several days. This decrease will make it look like things are getting better at the national level. Then, in the week following the holiday, our test, case, and death numbers will spike, which will look like a confirmation that Thanksgiving is causing outbreaks to worsen. But neither of these expected movements in the data will necessarily mean anything about the state of the pandemic itself. Holidays, like weekends, cause testing and reporting to go down and then, a few days later, to "catch up." So the data we see early next week will reflect not only actual increases in cases, test, and deaths, but also the potentially very large backlog from the holiday.

And indeed, new daily cases dropped from 183,000 on Wednesday to 125,000 on Thursday, rose to 194,000 on Friday, then dropped back to 152,000 on Saturday. Even in the states which still reported new cases, deaths, and tests on Thanksgiving, many testing sites and labs were closed, further contributing to reporting backlogs and discrepancies.

If you’re watching (or reporting) the numbers in your community, the Project recommends using seven-day averages—for example, rather than just looking at today’s new cases for evidence that the pandemic is slowing, calculate the average of today’s new cases and new cases from the six previous days. Current hospitalization figures and the hospital capacity data reported by the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) may also be more reliable, as hospitals don’t take days off.

Finally, I’d like to echo the COVID Tracking Project in thanking the many thousands of people behind these data. There are healthcare workers, lab technicians, public health leaders, and data pipeline IT workers behind every single number that you see in this newsletter. I am grateful for all of their efforts.

This newsletter is a labor of love for me each week. If you appreciate the news and resources, I’d appreciate a tip:

Who should get the first vaccine doses?

With this past Monday’s announcement from the University of Oxford and the pharmaceutical company AstraZeneca, three COVID-19 vaccine candidates have now demonstrated clinical trial results which could land them Emergency Use Authorization from the Food & Drug Administration (EUA from the FDA, for short). Pfizer, the first vaccine manufacturer to release its trial results, applied for EUA on November 20. The FDA advisory committee will meet on December 10 to review this application, and vaccines could start shipping out as early as December 12.

These dates are incredibly exciting—December 12 is only three weeks away. But that first vaccine shipment will likely include 50 million doses, at most. Since two doses are required for a patient to be protected against COVID-19, this means up to 25 million people will be able to get vaccinated. That represents just 7.6% of the country’s population. So, who will get vaccinated first?

As per usual in America’s fractured pandemic response, the answer to this question will largely depend on state and local public health authorities. Still, national guidances and data on health disparity allow us to see who should get the vaccine first—and evaluate our local public health authorities when the doses start rolling out.

Earlier this week, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) released a report which aims to help local authorities make these decisions. The ACIP is a group of medical and public health experts affiliated with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), which develops recommendations on how vaccines should be used among U.S. residents. The committee has been considering COVID-19 vaccine ethics since April, through a Work Group which conducted literature reviews and presented its findings to the rest of the team.

The ACIP recommends that four ethical principles guide COVID-19 vaccine distribution:

Maximize benefits and minimize harms. The first people to get vaccinated should be those who, when they are healthy, are better able to protect the health of others in their community. This includes healthcare workers, other essential workers, and people with preexisting health conditions who would likely need to be hospitalized if they became sick with COVID-19.

Promote justice. Americans of all backgrounds and communities should have an equal opportunity to be vaccinated. The ACIP recommends that public health authorities work with external partners and community representatives to help make vaccines available (and attractive) to everyone—both when vaccine supply is limited and when everyone is able to get inoculated.

Mitigate health inequities. People of color, especially Black Americans, Native Americans, and Native Hawaiians/Pacific Islanders, have been disproportionately impacted by COVID-19 in the U.S. The legacy of systemic racism in this nation’s healthcare system and economy, as well as disparities in testing availability and care, have contributed to these inequitable outcomes. Vaccine distribution must directly address such inequities by prioritizing racial and ethnic minorities, low-income communities, rural communities, and other marginalized groups.

Promote transparency. All the decisions that public health authorities make about who gets the vaccine, when, and how must be communicated clearly to the public. Furthermore, communities should be invited to participate in the decision-making process whenever possible. This kind of transparency helps promote trust in both the vaccines and the people who administer them.

The ACIP’s recommendations are also laid out more practically in two tables at the end of the report. The first table poses essential questions for public health authorities to consider for each ethical principle, while the second applies these principles to four key groups who will be prioritized in the first round of vaccinations: healthcare workers, other essential workers, adults with high-risk medical conditions, and adults over the age of 65.

Dr. Uché Blackstock, the founder of Advancing Health Equity, critiqued the recommendations on Twitter for failing to specifically call out the role of systemic racism in shaping how COVID-19 has impacted Black communities. Still, these principles are a good start in providing us reporters and community members with a framework for watching how our public health authorities distribute vaccines.

The federal government will simply be sending vaccine doses to states based on their overall populations rather than taking the ACIP’s recommendations, according to NPR’s Pien Huang. So, it will be entirely up to states and more local public health departments to prioritize justice, equity, and transparency. What tools should public health departments use in order to apply these principles?

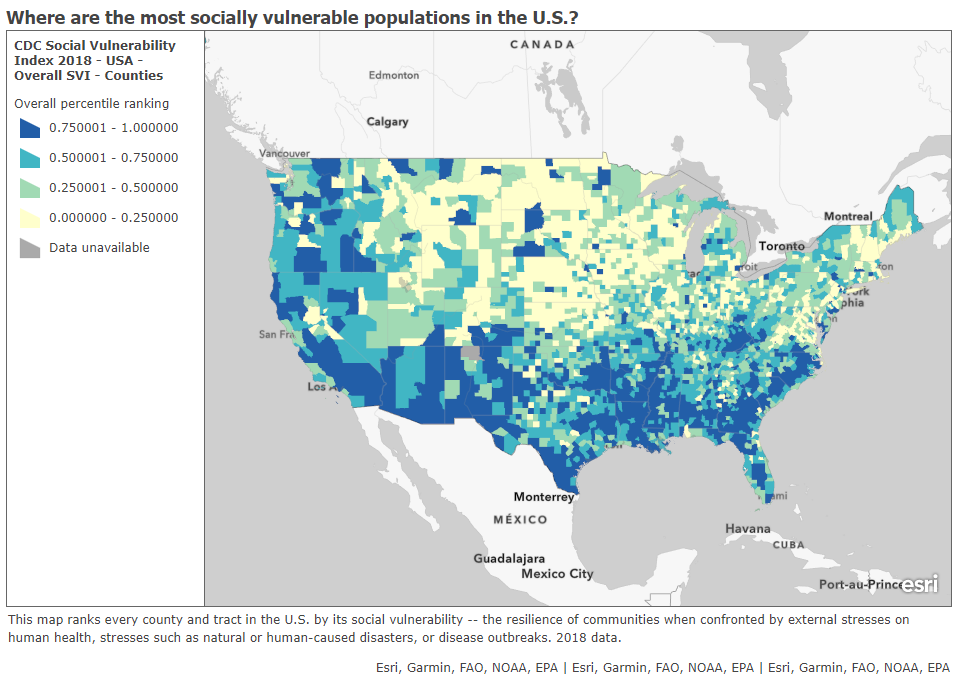

In a webinar last week on vaccine distribution, STAT News reporter Nicholas St. Fleur suggested turning to the CDC’s Social Vulnerability Index. Social vulnerability, as the CDC defines it, measures a community’s ability to recover from events that are hazardous to human health. These events can include tornados, chemical spills, and—of course—pandemics. CDC researchers have calculated the social vulnerability of every Census tract in the U.S. based on 15 social, economic, and environmental factors such as poverty, lack of vehicle access, and crowded housing.

The most recent update of this index was released in March 2020 based on analysis of 2018 Census data. Here’s what it looks like, mapped by Esri’s Urban Observatory:

Here’s the interactive map, and here’s the CDC page where you can download all the underlying data for this index. I highly recommend zooming in to your state and looking at which areas are ranked most highly—if COVID-19 vaccines are distributed equitably, these are the communities that should get priority.

St. Fleur also recommends checking out how your state, city, or county defines essential workers, as these distinctions may vary from region to region. In New York, for example, essential workers include teachers, pharmacists, and grocery store workers. In Texas, essential workers include law enforcement and the Texas Forest Service. The Kaiser Family Foundation report which I featured in last week’s issue compiles links to draft COVID-19 vaccination plans for every state, some of which include these definitions.

I anticipate that vaccine distribution and reporting will continue to be a major topic for this newsletter in the coming months. Questions and topic suggestions are always welcome; you can drop me a line at betsyladyzhets@gmail.com, on Twitter, or in the comments.

Thinking about vaccine results (AstraZeneca redux)

Two weeks ago, after Pfizer announced its preliminary results, I posed a set of questions that can guide how you understand the details in COVID-19 vaccine press releases.

I’m revisiting those questions now in the wake of AstraZeneca and the University of Oxford’s news. The 70% effectiveness rate announced last Monday is promising at first glance, but details about this vaccine’s clinical trials have puzzled epidemiologists. Here’s what to consider as we await more details on AstraZeneca and Oxford’s findings, drawing on reports from STAT News, Nature, and the New York Times.

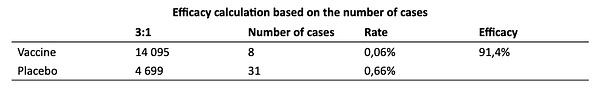

What is the sample size? Or, how many people were involved in the trial, and how many of them were diagnosed with COVID-19? AstraZeneca’s Monday announcement reported results from ongoing trials in the United Kingdom and Brazil, which include about 11,400 participants. 131 patients in the trial have tested positive for COVID-19. But here’s where things get tricky: out of those 11,400 participants, about 2,700 were given a lower dose of vaccine in their first shot due to an error in the U.K. trial. The other 8,900 trial participants received a standard two shots, i.e. two full doses of the vaccine. So, that 70% effectiveness rate is actually the average of results from two groups. In patients who received two full doses, the vaccine was 62% effective, while in patients who received a half dose and full dose, the vaccine was 90% effective.

Wait, the vaccine worked better in a lower dose? Yes—or at least, that’s what the data tell us so far. The researchers who made that dosing error may have gotten lucky by giving patients an initial dose which better stimulated their immune systems to act against the coronavirus. Nature’s Ewen Callaway quotes immunologists who say a lower dose might more effectively turn on T cells—immune cells that support antibody production—or more quickly activate the immune system’s memory of the virus. Still, the effectiveness rates we’ve seen for this vaccine so far may have been skewed by a small trial size; AstraZeneca has not reported how many patients among the 131 diagnosed with COVID-19 received a half-dose of the vaccine as compared to two full doses. AstraZeneca and Oxford will continue to study both the half-dose and full-dose regimens, and the scientific community eagerly awaits more data (and more details on how these trials are operating).

Who is included in the sample size? Or, has this vaccine been tested on seniors, people of color, people with preexisting medical conditions that may garner worse COVID-19 outcomes, and other marginalized groups? In addition to their U.K. and Brazil trials, AstraZeneca and Oxford are conducting trials in the U.S., Japan, Russia, South Africa, Kenya, and Latin America with planned trials in other nations, including up to 60,000 total participants. AstraZeneca’s press release states that these global trials include “participants aged 18 years or over from diverse racial and geographic groups”; no further information on participant demographics is available.

Does the vaccine work for severe cases? Or, can this vaccine help reduce COVID-19’s severity by boosting immune system defenses for patients who may otherwise get seriously ill? So far, it seems possible: no patients in AstraZeneca and Oxford’s initial analysis group went to the hospital or otherwise reported severe illness. But more results are needed for a conclusion to be made.

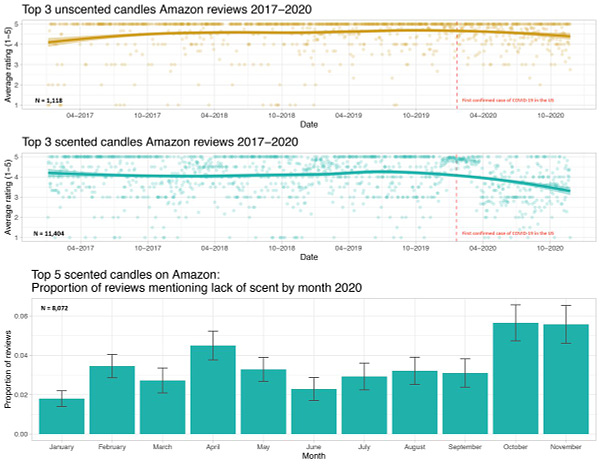

Does the vaccine work for mild or asymptomatic cases? Or, can this vaccine prevent people from spreading COVID-19 even if they don’t cough, sneeze, or otherwise show symptoms? AstraZeneca and Oxford are more poised to answer this question than other potential vaccine makers because participants in the U.K. trial have routinely tested themselves for the coronavirus, regardless of if they exhibited any symptoms. Results so far show that yes, this vaccine may block COVID-19 transmission—but again, more data are needed from a wider study group.

Does the vaccine have any adverse effects? Or, what might happen to you when you get the shot? Pfizer has reported that a small number of patients got headaches or felt fatigued after receiving their shots; Moderna has reported similar side effects as well as fever and muscle pain. AstraZeneca and Oxford have yet to report side effects from their vaccine, but their ongoing global trials will give the researchers more opportunity to see and communicate possible small hazards of the vaccination experience.

What are the vaccine’s logistical needs? Like Pfizer and Moderna’s vaccine candidates, AstraZeneca and Oxford’s vaccine requires two doses given weeks apart. Unlike the other two candidates, this vaccine can be stored in a normal refrigerator for up to six months, making it much easier to distribute—particularly to remote and low-income areas. It’s also easier to mass-produce, and AstraZeneca will only be charging $3 to $4 a dose, making it cheaper for governments to buy in bulk. (The U.S. government has promised that COVID-19 vaccines will be free to all Americans.) More logistical needs for all three vaccine candidates will be finalized in the coming months.

Meanwhile, in Russia, vaccine trial results have been reported after only 39 documented COVID-19 cases:

COVID-19 school data remain sporadic

On November 18, New York City mayor Bill de Blasio announced that the city’s schools would close until further notice. Students returned to remote learning, while restaurants and bars remain open—even indoor dining is permitted.

This closure came because the city had passed a 3% positivity rate. 3% of all tests conducted in the city in the week leading up to November 18 had returned positive results, indicating to the NYC Department of Health and de Blasio that COVID-19 is spreading rampantly in the community. As a result—and as de Blasio had promised in September—the city’s schools had to close.

But that 3% value is less straightforward than it first appears. In closing schools, de Blasio cited data collected by the NYC Department of Health, which counts new test results on the day that they are collected. The state of New York, however, which controls dining bans and other restrictions, counts new test results on the day that they are reported. Here’s how Joseph Goldstein and Jesse McKinley explain this discrepancy in the New York Times:

So if an infected person goes to a clinic to have his nose swabbed on Monday, that sample is often delivered to a laboratory where it is tested. If those results are reported to the health authorities on Wednesday, the state and city would record it differently. The state would include it with Wednesday’s tally of new cases, while the city would add it to Monday’s column.

Also, the state reports tests in units of test encounters while the city (appears to) report in units of people. (See my September 6 issue for details on these unit differences.) Also, the state includes antigen tests in its count, while the city only includes PCR tests. These small differences in test reporting methodologies can make a sizeable dent in the day-to-day numbers. On the day that Goldstein and McKinley’s piece was published, for example, the city reported an average test positivity rate of 3.09% while the state reported a rate of 2.54% for the city.

Meanwhile, some public health experts have questioned why a test positivity rate would be even used in isolation. The CDC recommends using a combination of test positivity, new cases, and a school’s ability to mitigate virus spread through contact tracing and other efforts. But NYC became fixated on that 3% benchmark; when the benchmark was hit, the schools closed.

Overall, the NYC schools discrepancy is indicative of an American education system that is still not collecting adequate data on how COVID-19 is impacting classrooms—much less using these data in a consistent manner. Science Magazine’s Gretchen Vogel and Jennifer Couzin-Frankel describe how a lack of data has made it difficult for school administrators and public health researchers alike to see where outbreaks are occurring. Conflicting scientific evidence on how children transmit the coronavirus hasn’t helped, either.

Emily Oster, a Brown University economist whom I interviewed back in October, continues to run one of a few comprehensive data sources on COVID-19 in schools. Oster has faced criticism for her dashboard’s failure to include a diverse survey population and for speaking as an expert on school transmission when she doesn’t have a background in epidemiology. Still, CDC Director Robert Redfield recently cited this dashboard at a White House Coronavirus Task Force briefing—demonstrating the need for more complete and trustworthy data on the topic. The COVID Monitor, another volunteer dashboard led by former Florida official Rebekah Jones, covers over 240,000 K-12 schools but does not include testing or enrollment numbers.

For me, at least, the NYC schools discrepancy has been a reminder to get back on the schools beat. Next week, I will be conducting a review of every state’s COVID-19 school data—including which metrics are reported and what benchmarks the state uses to declare schools open or closed. If there are other specific questions you’d like me to consider, shoot me an email or let me know in the comments.

We need better contact tracing data

Last week, New York Times reporter Apoorva Mandavilli questioned the scientific basis for recent public health guidance against small gatherings. Politicians and public health officials are telling us to cancel Thanksgiving dinners, she writes, but it’s difficult to find data that actually demonstrate a link between small gatherings and COVID-19 transmission.

Mandavilli acknowledges that the majority of states do not collect or report detailed information on how their residents became infected with COVID-19. This type of information would come from contact tracing, in which public health workers call up COVID-19 patients to ask about their activities and close contacts. Contact tracing has been notoriously lacking in the U.S. due to limited resources and cultural pushback.

I came to a similar conclusion about the contact tracing data deficiency in October, when I investigated the practice in this newsletter. Still, the data that are publicly available suggest that larger gatherings and congregate facilities are still the major sources of virus spread, as Mandavilli writes:

But in states where a breakdown is available, long-term care facilities, food processing plants, prisons, health care settings, and restaurants and bars are still the leading sources of spread, the data suggest.

The piece faced criticism for potentially undermining important guidances about the holidays. Even CDC Director Robert Redfield pushed back against it. When asked about this story on Fox News, he said, “From the data that we have, that the real driver now of this epidemic is not the public square… It’s really being driven by household gatherings.”

For me, this distinction between Mandavilli’s story and Redfield’s statement underscores that either a.) the CDC has access to some contact tracing data that the rest of us don’t, or b.) nobody has access to complete contact tracing data, and public health officials are communicating the conclusions that seem more politically salient. I don’t love either outcome!

The volunteer project Test and Trace compiles information on each state’s contact tracing efforts. Check out how your state is faring, and if you’re unsatisfied, contact your local politicians and ask them to do better.

Gaps we see in COVID-19 data

Last week, I asked readers to share what information or context gaps they see in COVID-19 coverage from other publications. Thank you to everyone who responded—these answers will be driving what I report on going forward.

Here are a couple of responses I’d like to highlight:

Two readers discussed a need for more local data. State-level reporting can obscure COVID-19 patterns at the county level, while even county-level data can obscure differences between urban, suburban, and rural areas in the same county. Some states do report data at the ZIP code or Census tract level, but this is—as you can probably guess—very unstandardized and difficult to compare broadly. President-Elect Joe Biden promises a Nationwide Pandemic Dashboard with ZIP code-level data, though; hopefully we may see this granular information come January.

One reader discussed a need for data on how COVID-19 is impacting K-12 schools, suggesting a section in each week’s newsletter. I wrote about schools this week, but they are definitely a topic that demands more coverage, especially as K-12 districts and higher ed institutions alike begin planning how they will tackle the spring semester. Expect to see more school data in the coming weeks!

Another reader said, “I do not have a good idea of how many people are really affected by COVID-19.” How many people were hospitalized or had long-term health issues as a result of the disease, and how much did the disease cost these patients? COVID-19 long-haulers—those who have the disease for many months—are an increasing topic of data collection, and many long-haulers are even collecting data on themselves. I can certainly feature them in a future newsletter. But I believe many long-term impacts, ranging from lost income to excess deaths, will not be fully understood until years after the pandemic.

A reader who works as a local journalist discussed how they see other reporters “failing to fundamentally understand data and how it’s used.” They went on to add, “Make every journalist take a data class.” I couldn’t agree more with this sentiment. Journo readers, keep an eye out for more resources (and possibly even events) that could help you out along these lines.

Featured sources

These sources, along with all others featured in previous weeks, are included in the COVID-19 Data Dispatch resource list.

Leading in Crisis briefs: A series of briefs from the Consortium for Policy Research in Education document how 120 principals in 19 states responded to COVID-19 in the spring. The briefs compile analyses, summaries, and recommendations on topics ranging from accountability during school closures to calm during a crisis.

COVID-19 in Congress: GovTrack.us. a project which normally documents bills and resolutions in the U.S. Congress, is currently tracking how COVID-19 has spread through the national legislature. The tracker currently includes 87 legislators who have entered quarantine, tested positive, or come into contact with someone who had been diagnosed with the disease.

COVID-19 Community Vulnerability Index: In the first vaccine section above, I discussed the CDC’s Social Vulnerability Index, which charts populations that are more vulnerable to health disasters. The Surgo Foundation’s COVID-19 Community Vulnerability Index builds on the CDC’s research with additional, COVID-specific metrics based on epidemiological and healthcare-related factors. I’ve produced two Stacker stories using this source: States with the populations most vulnerable to COVID-19 and Counties most vulnerable to COVID-19 in every state.

More recommended reading

Stacker Science & Health coverage

News from the COVID Tracking Project

Midwest Outbreaks Pause, Hospitalizations and Deaths Keep Rising: This Week in COVID-19 Data, Nov 25

Bonus

What Writing a Pandemic Newsletter Showed Me About America (WIRED)

‘They’ve been following the science’: How the Covid-19 pandemic has been curtailed in Cherokee Nation (STAT News)

12 writing tools to make COVID-19 coverage comprehensible. One stands above the rest. (Poynter)

That’s all for today! I’ll be back next week with more data news.

If you’d like to share this newsletter further, you can do so here: