The vaccines are coming

We might not have a COVID-19 vaccine by the election, but we'll likely have one before next spring. What data systems are in place to track vaccination, and what metrics should we look out for?

Welcome back to the COVID-19 Data Dispatch, where I read through 50-page public health documents so that you don’t have to.

This week, I’m unpacking the CDC’s new COVID-19 vaccination playbook from a data perspective and describing what I would like to see from sources once vaccination begins. Plus: updates to county-level testing data and school data, and a recent byline that I’m proud to share.

If you were forwarded this email, you can subscribe here:

Data reporting needs for COVID-19 vaccines

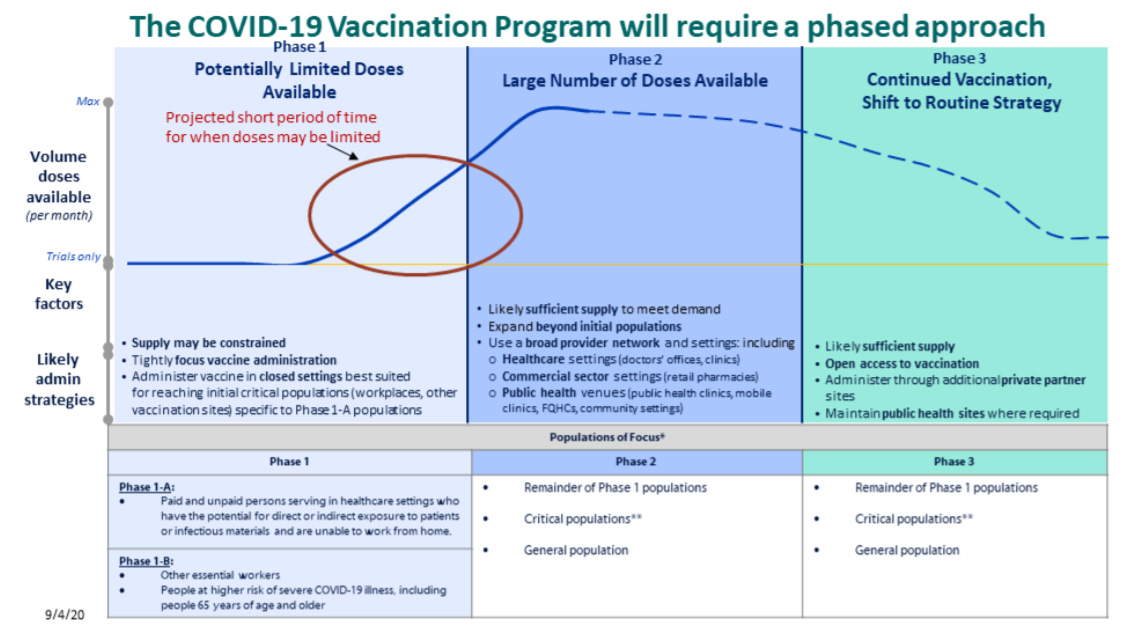

Graphic of questionable quality via the CDC’s COVID-19 Vaccination Program Interim Playbook

If the title of this week’s newsletter sounds ominous, that’s because this situation feels ominous. While many scientific experts have pushed back against President Trump’s claims that a vaccine for the novel coronavirus will be available this October, state public health agencies have been instructed to prepare for vaccine distribution starting in November or December.

Of course, the possibility of a COVID-19 vaccine before the end of 2020 is promising. The sooner healthcare workers and other essential workers can be inoculated, the better protected our healthcare system will be against future outbreaks. (And eventually, maybe, regular people like me will be able to attend concerts and fly out of the country again.) But considering the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)’s many missteps in both distributing and tracking COVID-19 tests this spring, I have a wealth of concerns about this federal agency’s ability to implement a national vaccination program.

I’m far from the only person thinking about this. The release of the CDC’s interim playbook for vaccine distribution this past Wednesday, along with President Trump’s public contradiction of the vaccination timeline described by CDC Director Dr. Robert Redfield, has sparked conversations on whether America could have a vaccine ready this fall and, if we do, what it would take to safely distribute this technology to the people who need it most.

In this issue, I will offer my takeaways on what the CDC’s playbook means for COVID-19 vaccination data, and a few key elements that I would like to see prioritized when public health agencies begin reporting on vaccinations.

Data takeaways from the CDC playbook

I’m not going to try to summarize the whole playbook here, because a. other journalists have already done a great job of this, and b. it would take up the whole newsletter. Here, I’m focusing specifically on what the CDC has told us about what vaccination data will be collected and how they will be reported.

We do not yet know which vaccines will be available, nor do we know vaccine volumes, timing, efficacy, or storage and handling requirements. It seems clear, however, that we should prepare for not just one COVID-19 vaccine but several, used in conjunction based on which vaccines are most readily available for a particular jurisdiction.

Vaccination will occur in three stages (as pictured in the above graphic). First, limited doses will go to critical populations, such as healthcare workers, other essential workers, and the medically vulnerable. Second, more doses will go to the remainder of those critical populations, and vaccine availability will open up to the general public. Finally, anyone who wants a vaccine will be able to get one.

“Critical populations,” as described by the CDC, basically include all groups who have been demonstrably more vulnerable to either contracting the virus or having a more severe case of COVID-19. The list ranges from healthcare workers, to racial and ethnic minorities, to long-term care facility residents, to people experiencing homelessness, to people who are under- or uninsured.

The vaccine will be free to all recipients.

Vaccine providers will include hospitals and pharmacies in the first phase, then should be expanded to clinics, workplaces, schools, community organizations, congregate living facilities, and more.

Most of the COVID-19 vaccines that may come on the market will require two doses, separated by 21 or 28 days. For each recipient, both doses will need to come from the same manufacturer.

Along with the vaccines themselves, the CDC will send supply kits to vaccine providers. The kits will include medical equipment, PPE, and—most notably for me—vaccination report cards. Medical staff are instructed to fill out these cards with a patient’s vaccine manufacturer, the date of their first dose, and the date by which they will need to complete their second dose. Staff and data systems should be prepared for patients to receive their two doses at two different locations.

All vaccine providers will be required to report data to the CDC on a daily basis. When someone gets a vaccine, their information will need to be reported within 24 hours. Reports will go to the CDC’s Immunization Information System (IIS).

The CDC has a long list of data fields that must be reported for every vaccination patient. You can read the full list here; I was glad to see that demographic fields such as race, ethnicity, and gender are included.

The CDC has set up a data transferring system, called the Immunization Gateway (or IZ Gateway), which vaccine providers can use to send their daily data reports. Can is the operative word here; as long as providers are sending in daily reports, they are permitted to use other systems. (Context: the IZ Gateway is an all-new system which some local public health agencies see as redundant to their existing vaccine trackers, POLITICO reported earlier this week.)

One resource linked in the playbook is a Data Quality Blueprint for immunization information systems. The blueprint prioritizes making vaccination information available, complete, valid, and timely.

Vaccine providers are also required to report “adverse events following immunization” or poor patient outcomes that occur after a vaccine is administered. These outcomes can be directly connected to the vaccine or unrelated; tracking them helps vaccine manufacturers detect new adverse consequences and keep an eye on existing side effects. Vaccine providers are required to report these adverse events to the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS), which, for some reason, is separate from the CDC’s primary IIS.

Once COVID-19 vaccination begins, the CDC will report national vaccination data on a dashboard similar to the agency’s existing flu vaccination dashboard. According to the playbook, this dashboard will include estimates of the critical populations that will be prioritized for vaccination, locations of CDC-approved vaccine providers and their available supplies, and counts of how many vaccines have been administered.

I have to clarify, though: all of the guidelines set up in the CDC’s playbook reflect what should happen when vaccines are implemented. It remains to be seen whether already underfunded and understaffed public health agencies, hospitals, and health clinics will be able to store, handle, and distribute multiple vaccine types at once, to say nothing of adapting to another new federal data system.

My COVID-19 vaccination data wishlist

This second section is inspired by an opinion piece in STAT, in which physicians and public health experts Luciana Borio and Jesse L. Goodman outline three necessary conditions for effective vaccine distribution. They argue that confidence around FDA decisions, robust safety monitoring, and equitable distribution of vaccines are all key to getting this country inoculated.

The piece got me thinking: what would be my necessary conditions for effective vaccine data reporting? Here’s what I came up with; it amounts to a wishlist for available data at the federal, state, and local levels.

Unified data definitions, established well before the first reported vaccination. Counts of people who are now inoculated should be reported in the same way in every state, county, and city. Counts of people who have received only one dose, as well as those who have experienced adverse effects, should similarly be reported consistently.

No lumping of different vaccine types. Several vaccines will likely come on the market around the same time, and each one will have its own storage needs, procedures, and potential effects. While cumulative counts of how many people in a community have been vaccinated may be useful to track overall inoculation, it will be important for public health researchers and reporters to see exactly which vaccine types are being used where, and in what quantities.

Demographic data. When the COVID Racial Data Tracker began collecting data in April, only 10 states were reporting some form of COVID-19 race and ethnicity data. North Dakota, the last state to begin reporting such data, did not do so until August. Now that the scale of COVID-19’s disproportionate impact on racial and ethnic minorities is well documented, such a delay in demographic data reporting for vaccination would be unacceptable. The CDC and local public health agencies will reportedly prioritize minority communities in vaccination, and they must report demographic data so that reporters like myself can hold them accountable to that priority.

Vaccination counts for congregate facilities. The CDC specifically acknowledges that congregate facilities, from nursing homes to university dorms to homeless shelters, must be vaccination priorities. Just as we need demographic data to keep track of how minority communities are receiving vaccines, we need data on congregate facilities. And such data should be consistently reported from the first phase of vaccination, not added to dashboards sporadically and unevenly, as data on long-term care facilities have been reported so far.

Easily accessible resources on where to get vaccinated. The CDC’s vaccination dashboard will reportedly include locations of CDC-approved vaccine providers. But will it include each provider’s open hours? Whether the provider requires advance appointments or allows walk-ins? Whether the provider has bilingual staff? How many vaccines are available daily or weekly at the site? To be complete, a database of vaccine providers needs to answer all the questions that an average American would have about the vaccination experience. And such a database needs to be publicized widely, from Dr. Redfield all the way to local mayors and school principals.

County-level test data gets an update

I spent the bulk of last week’s issue unpacking a new testing dataset released by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services which provides test positivity rates for U.S. counties. At that point, I had some unanswered questions, such as “When will the dataset next be updated?” and “Why didn’t CMS publicize these data?”

The dataset was updated this past week—on Thursday, September 17, to be precise. So far, it appears that CMS is operating on a two-week update schedule (the dataset was first published on Thursday, September 3). The data themselves, however, lag this update by a week: the spreadsheet’s documentation states that these data are as of September 9.

CMS has also changed their methodology since the dataset’s first publication. Rather than publishing 7-day average positivity rates for each county, the dataset now presents 14-day average positivity rates. I assume that the 14 days in question are August 27 through September 9, though this is not clearly stated in the documentation.

This choice was reportedly made “in order to use a greater amount of data to calculate percent test positivity and improve the stability of values.” But does it come at the cost of more up-to-date data? If CMS’s future updates continue to include one-week-old data, this practice would be antithetical to the actual purpose of the dataset: letting nursing home administrators know what the current testing situation is in their county so that they can plan testing at their facility accordingly.

Additional documentation and methodology updates include:

The dataset now includes raw testing totals for each county (aggregated over 14 days) and 14-day test rates per 100,000 population. Still, without total positive tests for the same time period, it is impossible to replicate the CMS’s positivity calculations.

As these data now reflect a 14-day period, counties with under 20 tests in the past 14 days are now classified as Green and do not have reported positivity rates.

Counties with low testing volume, but high positivity rates (over 10%), are now sometimes reassigned to Yellow or Green tiers based on “additional criteria.” CMS does not specify what these “additional criteria” may be.

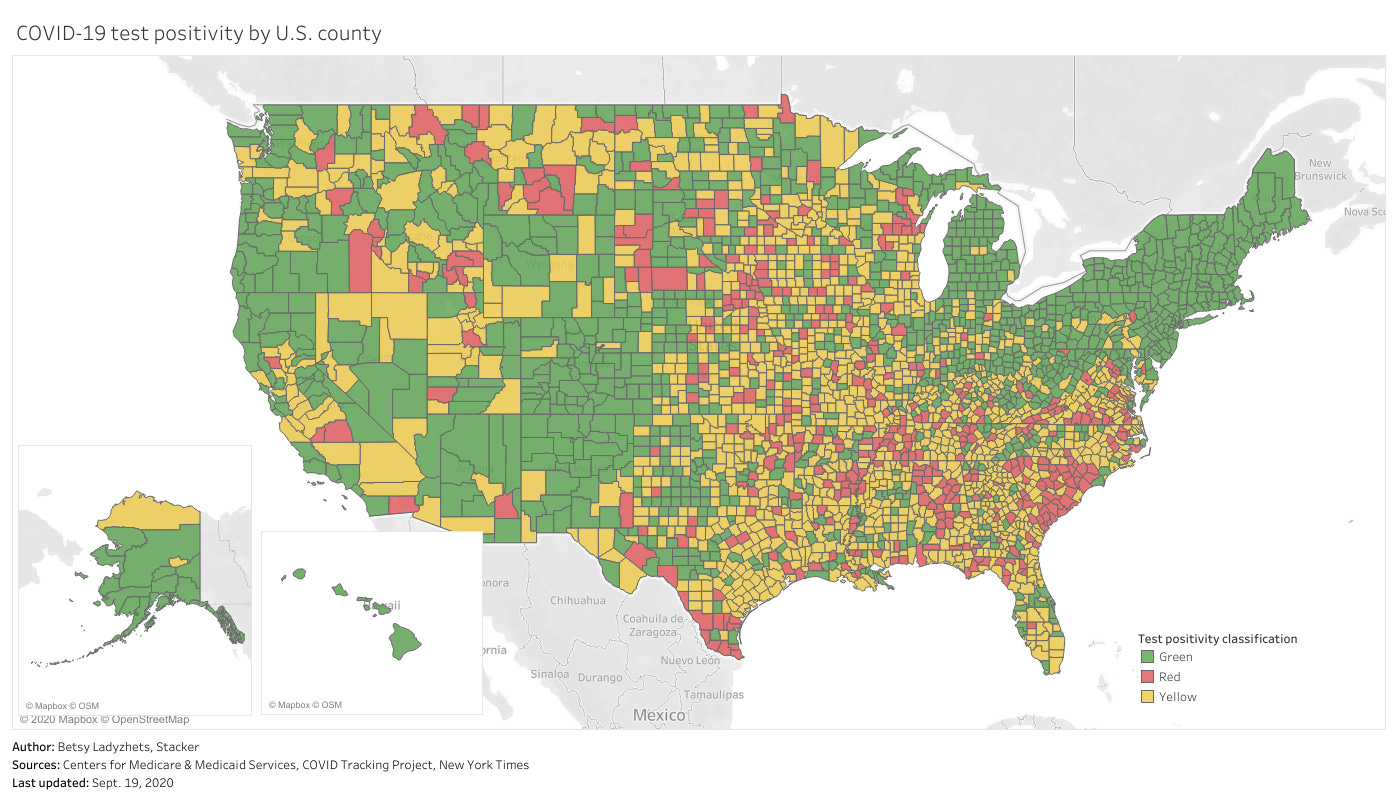

I’ve made updated versions of my county-level testing Tableau visualizations, including the new total test numbers:

This chart is color-coded according to CMS’s test positivity classifications. As you can see, New England is entirely in the green, while parts of the South, Midwest, and West Coast are spottier.

Finally: CMS has a long way to go on data accessibility. A friend who works as a web developer responded to last week’s newsletter explaining how unspecific hyperlinks can make life harder for blind users and other people who use screenreaders. Screenreaders can be set to read all the links on a page as a list, rather than reading them in-text, to give users an idea of their navigation options. But when all the links are attached to the same text, users won’t know what their options are. The CMS page that links to this test positivity dataset is a major offender: I counted seven links that are simply attached to the word “here.”

This practice is challenging for sighted users as well—imagine skimming through a page, looking for links, and having to read the same paragraph four times because you see the words “click here” over and over. (This is my experience every time I check for updates to the test positivity dataset.)

“This is literally a test item in our editor training, that’s how important it is,” my friend said. “And yet people still get it wrong. ALL THE TIME.”

One would think an agency dedicated to Medicare and Medicaid services would be better at web accessibility. And yet.

School data updates

The CDC was busy last week. In addition to their vaccination playbook, the agency released indicators for COVID-19 in schools intended to help school administrators make decisions about the safety of in-person learning. The indicators provide a five-tier system, from “lowest risk of transmission” (under 5 cases per 100,000 people, under 3% test positivity) to “highest risk” (over 200 cases per 100,000 people, over 10% test positivity). It is unclear what utility these guidelines will have for the many school districts that have already started their fall semesters, but, uh, maybe New York City can use them?

Speaking of New York: the state’s dashboard on COVID-19 in schools that I described in last week’s issue is now live. Users can search for a specific school district, then view case and test numbers for that district’s students and staff. At least, they should be able to; many districts, including New York City, are not yet reporting data. (The NYC district page reports zeros for all values as of my sending this issue.)

Los Angeles Unified, the nation’s second-largest school district, is building its own dashboard, the Los Angeles Times reported last week. The district plans to open for in-person instruction in November or later, at which point all students and staff will be tested for COVID-19. Test results down to the classroom level will be available on a public dashboard.

Wisconsin journalists have stepped in to monitor COVID-19 outbreaks in schools, as the state has so far failed to report these data. A public dashboard available via the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel and the USA Today Network allows users to see case counts and resulting quarantine and cleaning actions at K-12 schools across the state. Wisconsin residents can submit additional cases through a Google form.

According to the COVID Monitor, states that report K-12 COVID-19 case counts now include: Arkansas, Hawaii, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, New Hampshire, Ohio, South Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, and Utah. Some of these state reports are far more precise than others; Texas and Utah, for example, both report only total case counts. The COVID Monitor reports over 10,000 COVID-19 confirmed cases in K-12 schools as of September 20, with another 17,000 reported cases pending.

A recent article in the Chronicle of Higher Education by Michael Vasquez explains common issues with reporting COVID-19 cases on college and university campuses: inconsistencies across school dashboards, administrations unwilling to report data, and other challenges.

How to understand COVID-19 numbers

OG readers may remember that, in my first issue, I praised a ProPublica article by Caroline Chen and Ash Ngu which explains how to navigate and interpret COVID-19 data. I was inspired by that article to write a similar piece for Stacker: “How to understand COVID-19 case counts, positivity rates, and other numbers.”

I drew on my experience managing Stacker’s COVID-19 coverage and volunteering for the COVID Tracking Project to explain common COVID-19 metrics, principles, and data sources. The story starts off pretty simple (differentiating between confirmed and probable COVID-19 cases), then delves into the complexities of reporting on testing, outcomes, and more. As a reader of this newsletter, you likely already know much of the information in the story, but it may be a good article to forward to friends and family members who don’t follow COVID-19 data quite so closely.

(I also made a custom graphic for the “seven-day average cases” slide, which was a fun test of my burgeoning Tableau skills.)

Featured data sources

Dear Pandemic: This source describes itself as “a website where bona fide nerdy girls post real info on COVID-19.” It operates as a well-organized FAQ page on the science of COVID-19, run by an all-female team of researchers and clinicians.

Mutual Aid Disaster Relief: This past spring saw an explosion of mutual aid groups across the country, as people helped their neighbors with food, medical supplies, and other needs in the absence of government-sponsored aid. These groups may no longer be in the spotlight, but as federal relief bills continue to stall, they still need support. Organizations like Mutual Aid Disaster Relief can help you find a mutual aid group in your area.

COVID source callout

Utah was one of the first states to begin reporting antigen tests back in early August. The state is also one of only three to report an antigen testing time series, rather than simply the total number of tests conducted. However, the format in which Utah presents these data is… challenging.

Rather than reporting daily antigen test counts—or daily PCR test counts, for that matter—in a table or downloadable spreadsheet, Utah requires users to hover over an interactive chart in an extremely precise fashion. Interactive charts are useful for visualizing data, but far from ideal for accessibility.

Hot tip for anyone interacting with this chart: you can make your life easier by clicking “Compare data on hover,” toggling the chart to show all four of its daily data points at once. (Sad story: I did not learn this strategy until I’d already spent an hour carefully zooming in and around the chart to record all of Utah’s antigen test numbers.)

In related news: keep an eye out for a COVID Tracking Project blog post on antigen testing, likely to be published in the coming week.

More recommended reading

My recent Stacker bylines

Essential COVID-19 stats: Where testing, case counts, and outbreaks stand in your state (updated 9/17)

News from the COVID Tracking Project

State-level data obscures important variations in how cities and counties experience COVID-19

Holiday Reporting Lags Interrupt Positive Trends: This Week in COVID-19 Data, Sep 17

Bonus

That’s all for today! I’ll be back next week with more data news.

If you’d like to share this newsletter further, you can do so here:

If you have any feedback for me—or if you want to ask me your COVID-19 data questions—you can send me an email (betsyladyzhets@gmail.com) or comment on this post directly:

This newsletter is a labor of love for me each week. If you appreciate the news and resources, I’d appreciate a tip: