It's time to talk about antigen testing

Antigen testing is becoming an important diagnostic tool in outbreak areas such as nursing homes and the state of Texas. What data do we need to keep track of these tests?

Welcome back to the COVID-19 Data Dispatch, where a new set of numbers appearing on Texas’ COVID-19 dashboard is cause for celebration.

This week, I’ll explain everything you need to know about antigen testing, the hot new diagnostic tool gaining prevalence at outbreak sites across the country. I’ll also give you an update on HHS’s hospitalization data, because, of course, it’s still unreliable, and explain a tool you can use to help determine the COVID-19 risk level in your area.

This is a baby newsletter, so I would appreciate anything you can do to help get the word out. If you were forwarded this email, you can subscribe here:

Antigen tests: fast, cheap, and almost diagnostic

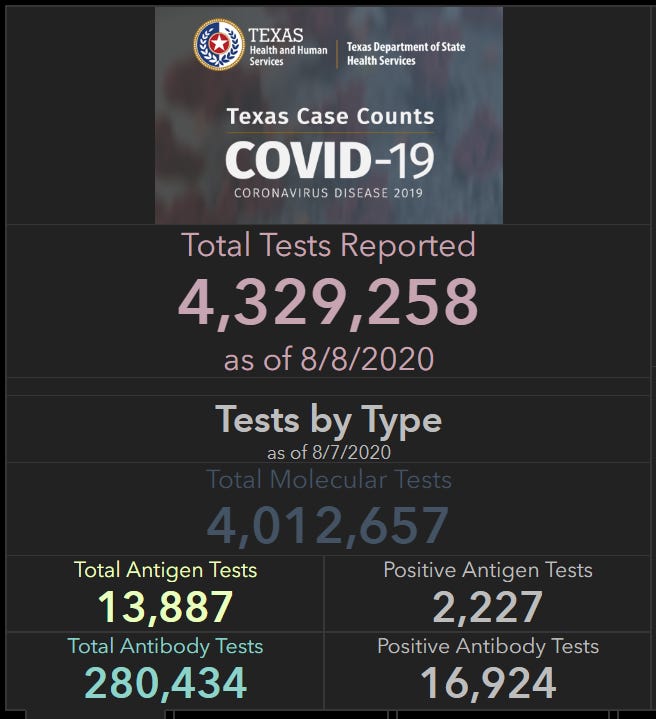

COVID-19 tests conducted in Texas as of August 8. Screenshot retrieved from the Texas Tests and Hospitals dashboard.

So far in this pandemic, there have been two main players for determining who has been infected with SARS-CoV-2, the virus which causes COVID-19.

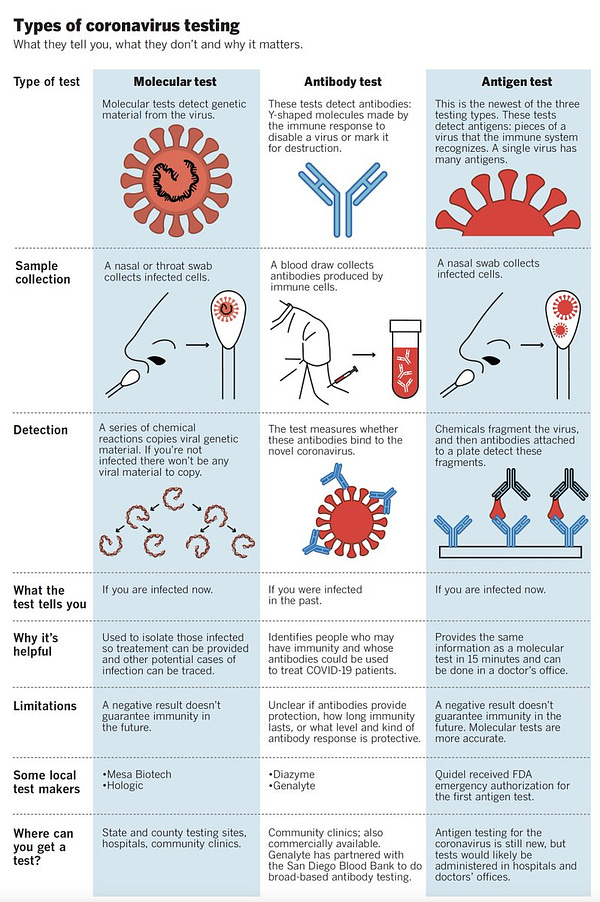

There are polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests, or molecular tests, which identify viral genetic material in a patient’s ear, nose, and throat cells. And there are antibody tests, or serology tests, which identify cells produced by a patient’s immune system response in their bloodstream. PCR tests are also called “diagnostic” tests, because they are used to conclusively diagnose patients with COVID-19.

If you get a positive PCR test result, you know that you currently have the disease; you should begin self-isolating and should tell anyone with whom you recently had in-person contact to do the same. Antibody tests, on the other hand, are not diagnostic: they identify patients who have built up an immune response to COVID-19, likely (but not certainly) because they were infected with it. If you get a positive antibody test result, your local public health department would likely count you as a “probable” or “suspected” case.

In May, however, a new type of testing came on the scene. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) authorized its first antigen test on May 9, and its second antigen test on July 6. By the end of July, both types of antigen tests had been distributed to hundreds of nursing homes across the country.

What are antigen tests? Antigen tests, like PCR tests, involve putting a swab up a patient’s nose. The swab takes a sample of potentially infected cells; the sample is then placed in a special chemical solution that breaks down the cells and flags the presence of antigens, unique pieces of the SARS-CoV-2 virus which normally live on the outside of the virus’ structure and are a key piece of immune system response. The testing process can be done in about fifteen minutes, and does not require the complex equipment needed to perform a PCR test.

This ten-minute video from Medmastery gives a detailed explanation of how antigen tests work. You can also see a brief overview of how antigen tests compare to PCR and antibody tests here:

Proponents of antigen tests suggest that these tests may one day become so readily available and so easy to use that high-risk workers and those in outbreak areas could test themselves before leaving the house. FDA leaders point out in their May 9 statement about the first authorized antigen test:

Antigen tests are also important in the overall response against COVID-19 as they can generally be produced at a lower cost than PCR tests and once multiple manufacturers enter the market, can potentially scale to test millions of Americans per day due to their simpler design, helping our country better identify infection rates closer to real time.

However, while antigen tests are technically diagnostic—they can tell you if you have COVID-19 right now—they do not meet the epidemiological gold standard for accurate testing. Antigen tests have a high specificity, meaning that they do not identify many false positives; if you receive a positive COVID-19 antigen test result, you can be pretty sure your result is correct. But they have a lower sensitivity than PCR tests, meaning that these tests may miss identifying people who are, in fact, infected with SARS-CoV-2. If you receive a negative COVID-19 antigen test result, but you have symptoms that match the disease or recently came into contact with someone who was infected, an epidemiologist would advise you to check your result by getting a PCR test.

Antigen tests are useful in quickly identifying COVID-19 patients who may be isolated and begin receiving treatment. And, once these tests are more readily available, they will useful in determining infection rates in a broad population. But because of that low test sensitivity, someone with a positive antigen test result cannot be considered a “confirmed case of COVID-19” by public health departments.

Who is conducting antigen tests? As I covered in last week’s issue of this newsletter, nursing homes are doing antigen tests, big time. On July 14, the Trump Administration and the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) announced that COVID-19 antigen tests would be distributed to nursing homes in hotspot areas. On July 31, the CDC’s Dr. Robert Redfield claimed in the congressional subcommittee hearing on national coronavirus response that nearly one million of these test kits had already been distributed.

The Associated Press reported on August 4 that, according to HHS’s Admiral Brett Giroir, this distribution program is on track to get 2,400 antigen test machines and test kits to go with them out to nursing homes by mid-August. However, the HHS’s supply only includes enough tests for most nursing homes to test all of their residents once, and all of their staff twice. Many nursing home administrators will need to make their own deals with suppliers, or get support from state public health departments, in order to continue doing antigen testing after their federal supplies run out.

Antigen tests are also gaining prominence in Texas, where high case rates have put testing in high demand. In an analysis for the Houston Chronicle, published on August 2, Matt Dempsey, Stephanie Lamm, and Jordan Rubio estimated that tens of thousands of COVID-19 cases had been identified by antigen tests across the state. This analysis was based on data from the 11 Texas counties that published independent antigen test counts as of August 2. Texas’ Department of State Health Services (DSHS) only includes cases confirmed by PCR tests in its official total case count—a decision which may be more epidemiologically valid, but has caused confusion at the local level:

On July 16, DSHS removed almost 3,500 cases from Bexar County’s case totals, saying the cases were “probable” and not confirmed because they were from antigen test results.

San Antonio officials pushed back.

“To be clear, this is not an ‘error’ in Metro Health’s reporting,” said Colleen Bridger, San Antonio’s interim director of public health, in a press release. “This is a disagreement over what should be reported in total counts.”

On August 8, DSHS began reporting antigen tests on its Texas Tests and Hospitals dashboard. The August 8 numbers include about 14,000 total antigen tests, with about 2,000 positive results. Based on the Houston Chronicle’s analysis, this is likely a significant undercount—but at least Texas is starting to publish some numbers.

How are antigen test results being reported nationally? Outside of Texas, antigen test numbers are hard to come by. As of the time I send this newsletter, only two other states report official antigen test counts: Kentucky and Utah. Kentucky reports 459 antigen tests as of August 8 (they do not report how many of these tests were positive). Utah reports about 5,000 people tested with antigen tests as of August 4, with about 500 of those people receiving a positive result.

At the COVID Tracking Project, we have an important procedure: when folks on the data entry team notice that something new is happening with COVID-19 data—say, a new type of test gets approved by the FDA, or hospitals undergo a major change in their reporting protocol—we ask our outreach team, a group of reporters affiliated with the project, to write to every state public health department and ask them how they’re dealing with the change. Most states public health departments have now received questions about antigen testing (and pool testing, but that’s the subject for another newsletter). Answers generally fall in the range of, “We’re not doing antigen testing,” “We’re not doing it at the state level but some commercial labs are,” and “We’re starting to monitor it and include positive antigen tests as probable cases.”

Pennsylvania is one example of the third approach:

It’s not bad that states are including positive antigen tests as probable cases—as I said earlier, antigen tests are not accurate enough to confirm a case of COVID-19. But when states combine results from different test types in a single count, it is difficult to accurately calculate test positivity rates, testing rates per population, and other important metrics. COVID Tracking Project founders Alexis Madrigal and Rob Meyer explained this issue in detail back in May, when some states (and the CDC) were combining PCR and antibody test results. The same basic principle still applies: each test is used for a different purpose and has a different level of accuracy, and so its results should be reported separately.

And what about those thousands of antigen tests that were distributed to nursing homes? As I reported in last week’s issue, the national Nursing Home COVID-19 Public File does not specify what types of tests nursing homes are using to identify cases, nor do state-reported datasets on COVID-19 in nursing homes. A FAQ document put out by the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) states that nursing homes are required to “report the results of the COVID-19 tests that they conduct to the appropriate federal, state, or local public health agencies.” This includes, presumably, state public health departments and the HHS. But it is unclear whether either HHS’s or CMS’s datasets will be adjusted to include antigen test counts. I reached out to CMS’s press office asking about these results, and have yet to receive a response.

This is likely only the beginning for antigen tests. Politico reported earlier today that Admiral Giroir “hopes to have 20 million rapid point-of-care tests available per month by September.” Scientists quoted in a recent New York Times article cite antigen tests as a key technology for improving America’s testing speed. Both manufacturers producing FDA-approved antigen tests, Quidel and BD, cite supply issues which will make it difficult for them to meet demand from nursing homes and local public health departments. Still, the federal government has made antigen tests a priority, and I predict that their prevalence will only grow. COVID-19 data producers must adjust their reporting accordingly.

How many COVID-19 cases are actively circulating in your community?

This section was inspired by a question my friend Abby messaged me yesterday. She asked:

How come there don't seem to be any stats on active cases? Obviously it's important to track new cases, but what I mostly want to know is, what is the likelihood that, if I run into someone on the street, they have COVID-19, and it doesn't seem like new cases tells me that.

In response, I explained that active cases are pretty difficult to track in a country that hasn’t even managed to set up robust contact tracing at national or state levels. To keep tabs of active cases, a public health department would essentially need to call all infected people in its jurisdiction at regular intervals. Those people would need to answer questions about how they’re doing, what symptoms they have, and if they had gotten tested recently. This type of tracking might be doable for some smaller counties, but it’s challenging in larger counties, areas with swiftly rising COVID-19 case counts, areas without sufficient testing capacity, areas with health disparities where some residents aren’t likely to answer a call from a contact tracer… you get the idea.

But it’s still possible to model how many people sick with COVID-19 are likely present in a community at a given time. Epidemiologists and statisticians can use a region’s new case rate—the number of people recently diagnosed with COVID-19—and other COVID-19 metrics, along with population density and demographic information, to estimate how many people in that region are currently infected. A recent analysis in the New York Times used this type of method to estimate how many infected students might come to schools across the country.

If you’d like to see the likely infection rate in your area, check out the COVID-19 Event Risk Assessment Planning Tool developed by researchers at the Georgia Institute of Technology and Applied Bioinformatics Laboratory. Select a state and an event size, and the tool will tell you how likely it is that someone sick with COVID-19 is at this event. For example, at a 50-person event in New York: 2.2% risk. At a 50-person event in Florida: 21.3% risk.

HHS hospitalization data: still questionable

I’m starting to think I should make HHS hospitalization data a weekly section of this newsletter.

In case you haven’t read my previous two issues, here’s the situation: in mid-July, hospitals stopped reporting their counts of COVID-19 patients to the CDC, and instead began reporting to the HHS. Since then, HHS’s national hospitalization dataset has been unreliable. HHS’s counts of currently hospitalized COVID-19 patients are far higher than the concurrent counts reported by state public health departments, and HHS’s numbers often rise and fall significantly from day to day without clear explanation.

I, along with other COVID Tracking Project (CTP) volunteers, have been monitoring both hospitalization counts daily—the two counts being, HHS’s numbers and state-reported numbers compiled by CTP. Rebecca Glassman (data entry volunteer and resident Florida expert) and I have drafted a blog post for CTP about the biggest discrepancies we’ve seen, which will be published in the next few days.

Here’s a little preview of the issues we’re calling out:

In six states, HHS’s counts of currently hospitalized COVID-19 patients are, on average, at least 150% higher than the state’s counts. These states include Maine, Arkansas, New York, Connecticut, New Hampshire, and Delaware.

Both Florida and Nevada saw unexplained spikes in their HHS counts which were not matched by corresponding spikes in state counts.

The state of Louisiana actually reports more currently hospitalized COVID-19 patients than HHS does, even though the definitions used by both sources suggest that this discrepancy should be the other way around.

Many states do not have publicly available or easy-to-find definitions for how currently hospitalized COVID-19 patients are classified.

HHS’s counts on August 6 were very low across the board, with significant drops in the number of hospitals reporting in every state.

If you are a local reporter in any of the states mentioned here and would like to investigate the discrepancies in your area, please reach out to me! I’m happy to share the data underlying this analysis.

COVID Source Callout

Analyzing COVID-19 data in Florida is like wading through a swamp with rocks in your backpack while wearing a hazmat suit and being shouted at by a hundred people who all think they can go faster than you.

There are so many problems with Florida’s data, that when Rebecca (mentioned above) and Olivier Lacan, another CTP volunteer, tried to draft a short blog post about what was wrong, they ended up writing about 3,000 words. Florida reports a test positivity rate without publishing the underlying numbers for their calculation, making it impossible for researchers to check the figures. Florida doesn’t report probable cases and deaths, which is recommended by the CDC. Florida is mixing its PCR and antigen test results (and likely including both in its test positivity rate. Florida fails to alert people using its COVID-19 website and dashboard when the state faces data issues. Florida literally fired a scientist at its public health department who refused to manipulate the state’s data.

But hey, at least their daily PDF reports are under 1,000 pages now.

More recommended reading

My recent bylines

News from the COVID Tracking Project

Bonus

One of Florida’s biggest disparities: How coronavirus spread in Pinellas’ Black community (Tampa Bay Times)

Nursing homes grapple with a dual crisis: preparing for hurricane season amid the Covid-19 pandemic (STAT)

Can a Cartoon Raccoon Keep Schoolkids Safe from COVID-19? (Scientific American)

Scientists rename human genes to stop Microsoft Excel from misreading them as dates (The Verge)

That’s all for today! I will be back next week with an interview with Delaware State Auditor Kathy McGuiness about the COVID-19 data auditing framework she helped develop.

If you’d like to share this baby newsletter further, you can do so here:

And if you have any feedback for me—or if you want to ask me your COVID-19 data questions—you can send me an email (betsyladyzhets@gmail.com) or comment on this post directly:

Hi Betsy - it sounds like Florida data sucks. Why does the CTP give Florida an "A" grade on its data?