Data reporting insights, underreported antigen tests

Sharing a recap of the data journalism session I led at Science Writers 2020. Plus: data on antigen tests are not standardized and underreported.

Welcome back to the COVID-19 Data Dispatch, where we are always learning how to better report data in these terrifying times.

This week, I’ve gotta be honest, I’m pretty wiped. The Science Writers 2020 virtual conference was a full slate of sessions on diversity, climate change, and other important topics—on top of my usual Stacker workload. So, today’s issue provides a rundown of the session I led on the intersections between data journalism and science writing.

I’m also sharing a brief summary of the COVID Tracking Project blog post I co-wrote on antigen testing, which was published earlier this week, and an update on hospitalization data.

As always, getting the word out about this newsletter is appreciated. If you were forwarded this email, you can subscribe here:

What I learned from my Science Writers session

The session I organized was called “Diving into the data: How data reporting can shape science stories.” Its goal was to introduce science writers to the world of data and to show them that this world is not a far-off inaccessible realm, but is rather a set of tools that they can add to their existing reporting skills.

The session was only an hour long, but I packed in a lot of learning. First, I gave a brief introduction to data journalism and my four panelists introduced themselves. Then, I walked the attendees through a tutorial on Workbench, an online data journalism platform. Finally, panelists answered questions from the audience (and a couple of questions from me). The session itself was private to conference attendees, but many of the materials and topics we discussed are publicly available, hence my summarizing the experience for all of you.

First, let me introduce the panelists (and recommend that you check out their work!):

Duncan Geere: writer, editor, information designer. His projects include a data visualization blog, pen plotter art, a newsletter, and the world’s first data sonification podcast.

Jessica Malaty Rivera: Science Communication Lead at the COVID Tracking Project and infectious disease epidemiologist at the COVID-19 Dispersed Volunteer Research Network.

Christie Aschwanden: freelance journalist and author of the NYT bestseller Good to Go: What the Athlete in All of Us Can Learn from the Strange Science of Recovery. Her latest story, for Nature, discusses the complicated premise of herd immunity.

Sara Simon: data reporter, software engineer for newsrooms, and, most recently, COVID Tracking Project volunteer. During the session, she discussed her investigative projects on Pennsylvania’s COVID-19 mortality data and Miss America pageants.

The Workbench tutorial that I walked through with attendees was one of two that I produced for The Open Notebook this year, in association with my instructional feature on data journalism for science writers. Both workflows are designed to give science writers (or anyone else interested in science data) some basic familiarity with common science data sources and with the steps of cleaning and analyzing a dataset. You can read more about the tutorials here. If you decide to try them out, I am available to answer any questions that you have—either about Workbench as a whole or the choices behind these two data workflows. Just hit me up on Twitter or at betsyladyzhets@gmail.com.

I wasn’t able to take many notes during the session, of course, but if there’s one thing I know about science writers, it’s that they love to livetweet. (Conference organizers astutely requested that each session organizer pick out a hashtag for their event, to help keep the tweets organized. Mine was #DataForSciComm.)

Here are two great threads you can read through for the highlights:

Although some attendees had technical difficulties with Remo, Workbench, or both, I was glad to see that a few people did manage to follow the tutorial along to its final step: a bar chart showcasing American cities which have seen high particle pollution days in 2019.

Finally, I’d like to share a few insights that I got from the panelists’ conversation during our Q&A. As an early-career journalist myself, I always jump at the chance to learn from those I admire in my field—and yes, okay, I did invite four of them to a panel partially in order to manufacture one of those opportunities. The conversation ranged from practical questions about software tools to more ethical questions, such as how journalists can ensure their stories are being led by their data, rather than the other way around.

These are the main conclusions I took for my own work:

Use the simplest tool for the job, but make sure it does work for that job. I was surprised to hear all four panelists say that they primarily use Google Sheets for their data work, as I sometimes feel like I’m not a “real data journalist” due to my inexperience with coding. (I’m working on learning R, okay?) But they also acknowledged that simpler tools may cause problems, such as the massive reporting error recently seen by England’s public health department thanks to reliance on Microsoft Excel.

Fact-checking is vital. Data journalists must be transparent about both the sources they use and the steps they take in analysis, and fact-checkers should go through all of those steps before a big project is published—just as fact-checkers need to check every quote and assertion in a feature.

A newsroom’s biggest stories are often data stories. Many publications now are seeing their COVID-19 trackers or other large visualizations get the most attention from readers. Data stories can bring readers in and keep them engaged as they explore an interactive feature or look for updates to a tracker, which can often make them worth the extra time and resources that they take compared to more traditional stories.

There’s a data angle to every story. Sara Simon talked about building her own database for her Miss America project, and how this process prepared her for more thorough coverage when she actually attended a pageant. Sometimes, a data story is not based around an analysis or visualization; rather, building a dataset out of other information can help you see trends which inform a written story.

Collaboration is key. Duncan Geere talked about finding people whose strengths make up for your weaknesses, whether that is their knowledge of a coding language or their eye for design. Now, I’m thinking about what kind of collaborations I might be able to foster with this newsletter. (If you’re reading this and you have an idea, hit me up!)

COVID-19 data analysis requires time, caution, and really hard questions. Jessica Malaty Rivera talked about the intense editing and fact-checking process that goes into COVID Tracking Project work to ensure that blog posts and other materials are as accurate and transparent as possible. Hearing about this work from a more outside perspective stuck with me because it reminded me of my goals for this newsletter. Although I work solo here, I strive to ask the hard questions and lift up other projects and researchers that are excelling at accuracy and transparency work.

If you attended the session, I hope you found it informative and not too fast-paced. If you didn’t, I hope this recap gave you an idea of how data journalism and science communication may work together to tell more complex and engaging stories.

It is, once again, time to talk about antigen testing

Long-term readers might remember that I devoted an issue to antigen testing back in August. Antigen tests are rapid, diagnostic COVID-19 tests that can be used much more quickly and cheaply than their polymerase chain reaction (PCR) counterparts. They don’t require samples to be sent out to laboratories, and some of these tests don’t even require specialized equipment; Abbott’s antigen test only takes a swab, a testing card, and a reagent, and results are available in 15 minutes.

But these tests have lower sensitivity than PCR tests, meaning that they may miss identifying people who are actually infected with COVID-19 (what epidemiologists call false negatives). They’re also less accurate for asymptomatic patients. In order to carefully examine the potential applications of antigen testing, we need both clear public messaging on how the tests should be used, and accessible public data on how the tests are being used already. Right now, I’m not seeing much of either.

When I first covered antigen testing in this newsletter, only three states were publishing antigen test data. Now, we’re up past ten states with clear antigen test totals, with more states reporting antigen positives or otherwise talking about these tests in their press releases and documentation. Pennsylvania, for example, announced that the governor’s office began distributing 250,000 antigen test kits on October 14.

Meanwhile, antigen tests have become a major part of the national testing strategy. Six tests have received Emergency Use Authorization from the FDA. After Abbott’s antigen test was given this okay-to-distribute in late August, the White House quickly purchased 150 million tests and made plans to distribute them across the country. Context: the U.S. has done about 131 million total tests since the pandemic began, according to the COVID Tracking Project’s most recent count.

Clearly, antigen testing is here—and beginning to scale up. But most states are ill-prepared to report the antigen tests going on in their jurisdictions, and federal public health agencies are barely reporting them at all.

I’ve been closely investigating antigen test reporting for the past few weeks, along with my fellow COVID Tracking Project volunteers Quang Nguyen, Kara Schechtman, and others on the Data Quality team. Our analysis was published this past Monday. I highly recommend you give it a read—or, if you are a local reporter, I highly recommend that you use it to investigate antigen test reporting in your state.

But if you just want a summary, you can check out this Twitter thread:

And I’ve explained the two main takeaways below.

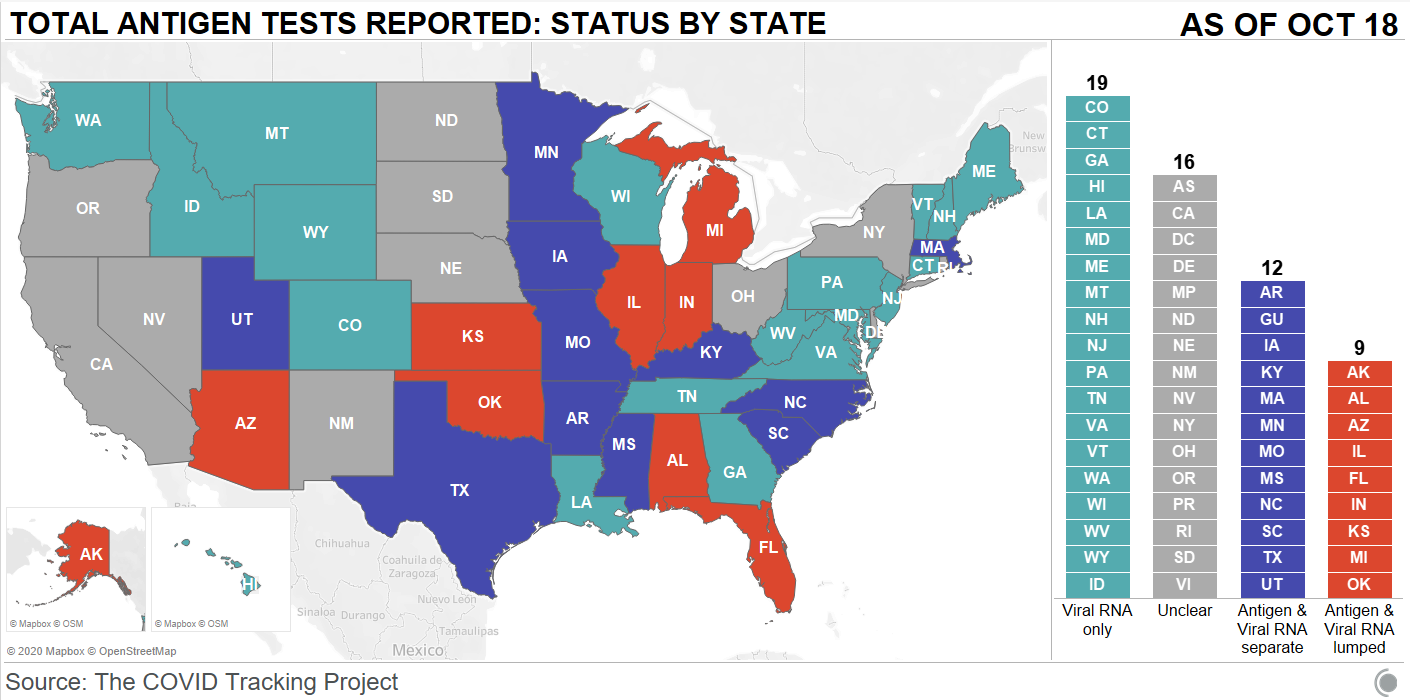

First: state antigen test reporting is even less standardized than PCR test reporting. While twelve states and territories do report antigen test totals, nine are combining their antigen test counts with PCR test counts, which makes it difficult to analyze the use of either test type or accurately calculate test positivity rates. The reporting practices in sixteen other states are unclear. And even among those states with antigen test totals, many relegate their totals to obscure parts of their dashboards, fail to publish time series, report misleading test positivity rates, and engage in other practices which make the data difficult for the average dashboard user to interpret.

Second: antigen tests reported by states likely represent significant undercounts. Data reporting inconsistences between the county and state levels in Texas, as well as a lack of test reporting from nursing homes, suggest that antigen tests confuse data pipelines. While on-site test processing is great for patients, it cuts out a lab provider which is set up to report all COVID-19 tests to a local health department. Antigen tests may thus be conducted quickly, then not reported. The most damning evidence for underreporting comes from data reported by test maker Quidel. Here’s how the post explains this:

Data shared with Carnegie Mellon University by test maker Quidel revealed that between May 26 and October 9, 2020, more than 3 million of the company’s antigen tests were used in the United States. During that same period, US states reported less than half a million antigen tests in total. In Texas alone, Quidel reported 932,000 of its tests had been used, but the state reported only 143,000 antigen tests during that same period.

Given that Quidel’s antigen test is one of six in use, the true number of antigen tests performed in the United States between late May and the end of September was likely much, much higher, meaning that only a small fraction are being reported by states.

Again: this is for one of six tests in use. America’s current public health data network can’t even account for three million antigen tests—how will it account for 150 million?

And, for some bonus reading, here’s context from the Associated Press about the antigen test reporting pipeline issue.

HHS changes may drive hospitalization reporting challenges

This past week, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) opened up a new area of data reporting for hospitals around the country. In addition to their numbers of COVID-19 patients and supply needs, hospitals are now asked to report their numbers of influenza patients, including flu patients in the ICU and those diagnosed with both flu and COVID-19.

The new reporting fields were announced in an HHS directive on October 6. They became “available for optional reporting” this past Monday, October 19; but HHS intends to make the flu data fields mandatory in the coming weeks. The move makes sense, broadly speaking—as public health experts worry about double flu and COVID-19 outbreaks putting incredible pressure on hospital systems, collecting data on both diseases at once can help the federal public health agencies quickly identify and get aid to the hospitals which are struggling.

However, it seems likely that the new fields have caused both blips in HHS data and challenges for the state public health departments which rely upon HHS for their own hospitalization figures. As the COVID Tracking Project (and this newsletter) reported over the summer, any new reporting requirement is likely to strain hospitals which are understaffed or underprepared with their in-house data systems. Such challenges at the hospital level can cause delays and inaccuracies in the data reported at both state and federal levels.

This week, the COVID Tracking Project’s weekly update called attention to gaps in COVID-19 hospitalization data reported by states. Missouri’s public health department specifically linked their hospitalization underreporting to “data changes from the US Department of Health and Human Services.” Five other states—Kansas, Wisconsin, Georgia, Alabama, and Florida—also reported significant decreases or partial updates to their hospitalization figures. These states didn’t specify reasons for their hospitalization data issues, but based on what I saw over the summer, I believe it is a reasonable hypothesis to connect them with HHS’s changing requirements.

Jim Salter of the Associated Press built on the COVID Tracking Project’s observations by interviewing state public health department officials. He reported that, in Missouri, some hospitals lost access to HHS’s TeleTracking data portal:

Missouri Hospital Association Senior Vice President Mary Becker said HHS recently implemented changes; some measures were removed from the portal, others were added or renamed. Some reporting hospitals were able to report using the new measures, but others were not, and as a result, the system crashed, she said.

“This change is impacting hospitals across the country,” Becker said in an email. “Some states collect the data directly and may not yet be introducing the new measures to their processes. Missouri hospitals use TeleTracking and did not have control over the introduction of the changes to the template.”

As the nation sets COVID-19 records and cases spike in the Midwest, the last thing that public health officials should be worrying about right now is inaccurate hospitalization data. And yet, here we are.

Featured data sources

Missing in the Margins: Estimating the Scale of the COVID-19 Attendance Crisis: This new report by Bellwether Education Partners provides estimates and analysis of the students who have been unable to participate in virtual learning during the pandemic. While the state-by-state estimates and city profiles may be useful to local reporters, the overall numbers should shock us all: three million students, now left behind.

The Pandemic and ICE Use of Detainers in FY 2020: The Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse (or TRAC) at Syracuse University has collected data on U.S. immigration since 2006. The project’s most recent report describes the pandemic’s impact on Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE)’s practice of detaining individuals as a step for apprehending and deporting them.

COVID-19 Risk Levels Dashboard: This dashboard by the Harvard Global Health Institute and other public health institutions now includes COVID-19 risk breakdowns at the congressional district level. Toggling back and forth between the county and congressional district options allows one to see that, when risk is calculated by county, a few regions of the U.S. are in the “green”; at the congressional district level, this is not true for a single area.

COVID-19 at the White House: VP Outbreak: The team behind a crowdsourced White House contact tracer (discussed in my October 4 issue) is now tracking cases connected to Vice President Mike Pence.

These sources have been added to the COVID-19 Data Dispatch resource list, along with all sources featured in previous weeks.

COVID source callout

To the tune of “Iowa Stubborn” from Meredith Wilson’s The Music Man:

And we’re so good at updating,

We can shift our case count

Twice every hour

With no timestamp to make a dent.

But we’ll give you our case counts,

And demographics to go with it

If you should love hovering over percents!So what the heck, you’re welcome,

Glad to have you checking,

Even though we may not ever mention it again.

You really ought to give Iowa… a try.

Parody lyrics aside, Iowa’s frequent dashboard updates are very impressive. But a little transparency about precisely when those updates occur would go a long way.

More recommended reading

Stacker health content

News from the COVID Tracking Project

Bonus

Schoolchildren Seem Unlikely to Fuel Coronavirus Surges, Scientists Say (New York Times)

Analysis: Why It’s So Hard to Spot NYC’s Next Coronavirus Hot Zones Using Public Stats (The City NYC)

That’s all for today! I’ll be back next week with more data news.

If you’d like to share this newsletter further, you can do so here:

If you have any feedback for me—or if you want to ask me your COVID-19 data questions—you can send me an email (betsyladyzhets@gmail.com) or comment on this post directly:

Fill out my survey to share your topic suggestions and questions:

This newsletter is a labor of love for me each week. If you appreciate the news and resources, I’d appreciate a tip: